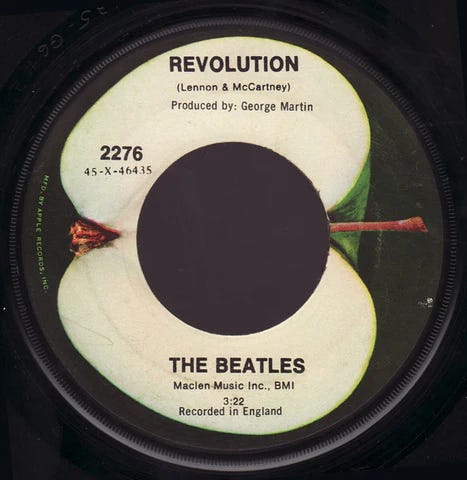

Revolution by The Beatles stands as one of the band’s most politically charged and controversial songs, marking a significant departure from their earlier, more lighthearted releases.

The song first appeared as the B-side to “Hey Jude,” released on August 26, 1968, and was later featured on the band’s self-titled double album (commonly known as the White Album) on November 22, 1968. Revolution emerged during a period of intense social and political unrest.

John Lennon, the primary songwriter behind Revolution, began writing the song in early 1968, inspired by events such as the intensity of the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and the assassinations of prominent figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. Lennon felt compelled to address these issues through his music.

The “fifth Beatle” and “the giggling guru”

Brian Epstein, often referred to as the “fifth Beatle,” played a crucial role in shaping The Beatles’ early career, securing recording contracts and guiding them from a local Liverpool band to an international sensation.

On August 24, 1967, The Beatles met Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who was lecturing on Transcendental Meditation in London. They were introduced by Epstein, who believed the Maharishi’s teachings could offer the band spiritual growth. Just three days later, on August 27, Epstein passed away.

In the wake of Epstein’s death, Lennon and the band found themselves without clear guidance and direction, which led them to become more experimental with their music.

In February 1968, the band traveled to Rishikesh, India, to study with the Maharishi. Their stay lasted less than three months but deeply influenced their outlook and music. The band also nicknamed Maharishi Mahesh Yogi “the giggling guru” because of his high-pitched laugh, cheerful demeanor, and the way he sometimes giggled while speaking.

This transitional period is significant to the context of Revolution, as Lennon began to look beyond traditional pop music to express his thoughts on politics and social change. Without Epstein’s guiding influence, Lennon felt free to address his perspective on the world.

“I wanted to put out what I felt about revolution,” Lennon stated. “I thought it was about time we spoke about it, the same as I thought it was about time we stopped not answering about the Vietnamese war when we were on tour with Brian Epstein and had to tell him, ‘We’re going to talk about the war this time, and we’re not going to just waffle.’ That’s why I did it: I wanted to talk, I wanted to say my piece about revolutions. I wanted to tell you, or whoever listens, to communicate, to say, ‘What do you say?’ ‘This is what I say.'”

A Revolution Trio

There are three versions of Revolution by The Beatles: the slower, bluesy Revolution 1 from The White Album (released on November 22, 1968), the avant-garde sound Revolution 9 (also from The White Album) representing an abstract conceptual revolution, and the faster, hard-rock version released as the B-side to Hey Jude on August 26, 1968.

As Lennon explained on The Dick Cavett Show in 1971, “There’s three versions. Number one, the slow one; number nine is an abstract picture of revolution. Number two was the single because the other boys didn’t like number one. They said it wasn’t fast enough, so I made it fast.”

Lyrically: Revolution by The Beatles

Before Lennon’s opening lyrics in Revolution, Paul McCartney’s low, guttural scream sets the tone, adding a sense of frantic emotion and attention.

Lyrically, Lennon begins with, “You say you want a Revolution, well, you know, we all wanna change the world,” acknowledging a collective desire for change.

The line “You tell me that it’s evolution” contrasts the shift of revolution with gradual change, just like an evolution. Lennon questions whether transformation should be forced through upheaval or unfold naturally.

The voice, or message, that Lennon “wanted to talk” to the world about, which he felt somewhat limited to express until this song, started with the line “But when you talk about destruction, don’t you know that you can count me out.”

During the recording of the song, Lennon sang “in” right after “out,” sounding like this: “But when you talk about destruction, don’t you know that you can count me out—in.”

By rejecting violence (“count me out”) while leaving room for reconsideration (“in”), Lennon expresses his internal conflict over the methods used during revolutionary moments. His delivery of “in,” almost as an aside, shows that while he supports change, he questions whether using destruction is a path to progress.

“I don’t believe in violent revolution either. Yoko stated it very well, which is: violent revolutionaries are playing the same establishment game. I believe in some of the things Jerry Rubin and maybe Hoffman have done, like the theater-in-court kind of revolution. I believe in the revolution of happening, and that artists—Yoko says artists don’t create; a woman or any man can destroy the Coke bottle and artistry values. If I’m a revolutionary, or we are revolutionaries, we are revolutionary artists, not gunmen,” Lennon explained. “I believe in the Black Panther’s original statement, the ten-point program, which is not violent, and says to defend yourself against attack. I might consider that, but anything else I don’t consider. So, I’m still for peace, a peaceful revolution, but I’m an artist first and a politician second.”

Lennon and Yoko Ono first met in November 1966 at the Indica Gallery in London, where Ono was preparing her art exhibit Unfinished Paintings and Objects. By 1968, their relationship had deepened both personally and creatively, coinciding with the end of Lennon’s six-year marriage to Cynthia Lennon. Ono’s influence reframed Lennon’s worldview and music, making his work more introspective and politically outspoken.

Don’t you know it’s gonna be alright

Alright

Alright

The lyrics “Don’t you know it’s gonna be alright, alright, alright” express Lennon’s optimism that positive change is possible without violence.

You say you got a real solution

Well, you know

We’d all love to see the plan

You ask me for a contribution

Well, you know

We are doing what we canBut if you want money for people with minds that hate

All I can tell you is brother you have to waitDon’t you know it’s gonna be alright

Alright

Alright

“You say you got a real solution, well, you know, we’d all love to see the plan” express Lennon’s skepticism about revolutionary ideas without a clear plan in place.

“I think all our society is run by insane people for insane objectives, and I think that’s what I sensed when I was 16 and, way down the line, but I expressed it differently all through my life,” said Lennon. “It’s the same thing I’m expressing all the time, but now I can put it into that sentence: I think we’re being run by maniacs for maniacal means. If anybody can put on paper what our government, the American government, etc., and the Russian, China—what they are actually trying to do, you know, or what they think they’re doing, I’d be very pleased to know what they think they’re doing. I think they’re all insane, you know, but I’m liable to be put away as insane for expressing that. You know, that’s what’s insane about it.”

The inclusion of the lyric “You ask me for a contribution, well, you know, we are doing what we can” shows his willingness to support causes, but with limits. The line “But if you want money for people with minds that hate, all I can tell you is brother, you have to wait” rejects movements that are fueled by hatred.

“Don’t you know it’s gonna be alright” once again reminds those listening that everything will work out based on the actions taken.

You say you’ll change the constitution, well, you know,

We all want to change your head

You tell me it’s the institution, well, you know,

You’d better free your mind instead

These lyrics suggest that real transformation begins with the individual. Changing one’s mindset (“change your head”) is a foundational step. After that, you can work on changing rules and systems. “Free your mind instead” calls for personal liberation as the foundation for meaningful societal change.

But if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao

You ain’t going to make it with anyone anyhow

In 1968, Chairman Mao Zedong was leading the Cultural Revolution in China, aimed at purging society of capitalist and traditional elements. The movement caused chaos, with widespread persecution, violence, and public humiliation of perceived enemies. Mao’s Red Guards, mainly young people, targeted intellectuals and anyone linked to “old” values, leading to fear and suffering across the country. While some supported Mao’s reforms, others became victims of his harsh policies.

Lennon’s lyrics question blindly following such radical figures, suggesting that meaningful change should not be based on violence or extreme ideology.

“The thing is, I regret making a reference to Chairman Mao, which might spoil any chances I have of visiting China… I’d love to go and see what’s happening there. But I wrote the Chairman Mao line in the studio because I didn’t have any words,” said Lennon on The Dick Cavett Show in 1971.

Lennon continued, “What I was trying to say to the Maoists or anybody that wanted to change the world was: why go and stand in front of a policeman with a red Communist flag in your hand and a big suit, more like that, and then get hit? I thought it was unsubtle. So, in the song, I wasn’t putting down revolution. I was saying, ‘Isn’t that a bit unsubtle?’ But if you really want to change the thing, do it subtly, in a way that the establishment can’t attack, i.e., theatre in court and/or bed events… things like that, things that the establishment don’t understand, therefore they can’t kill it.”

“I think he wanted to say you can count me in for a revolution, but if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao ‘you ain’t gonna make it with anyone anyhow.’ By saying that, I think he meant we all want to change the world Maharishi-style,” said McCartney. “I don’t think he was sure which way he felt about it at the time, but it was an overtly political song about revolution and a great one. I think John later ascribed more political intent to it than he actually felt when he wrote it.”

Don’t you know it’s gonna be alright

Alright

AlrightAlright, alright

Alright, alright

Alright, alright

Alright, alright

The final lyrics of Revolution—”Don’t you know it’s gonna be alright, alright, alright” repeated several times—serve as an affirmation that everything will ultimately work out and unfold the way it’s supposed to.

Revolution is a constant reminder that change is possible without violence.

Revolution was never performed live by the band. However, on September 4, 1968, The Beatles filmed a promotional video for Revolution at Twickenham Film Studios in London. The performance was filmed multiple times from different angles, creating what’s considered one of the earliest music videos in rock history. Since the band had stopped touring in 1966, this gave fans a rare glimpse of them performing together.

“Those who attacked the Beatles for their singing Revolution should be set down with a good pair of earphones,” stated Jann Wenner in Rolling Stone. “To say the Beatles are guilty of some kind of revolutionary heresy is absurd; they are being absolutely true to their identity as it has evolved through the last six years. These songs do not deny their own political impact or desires; they just indicate the channeling for them.”

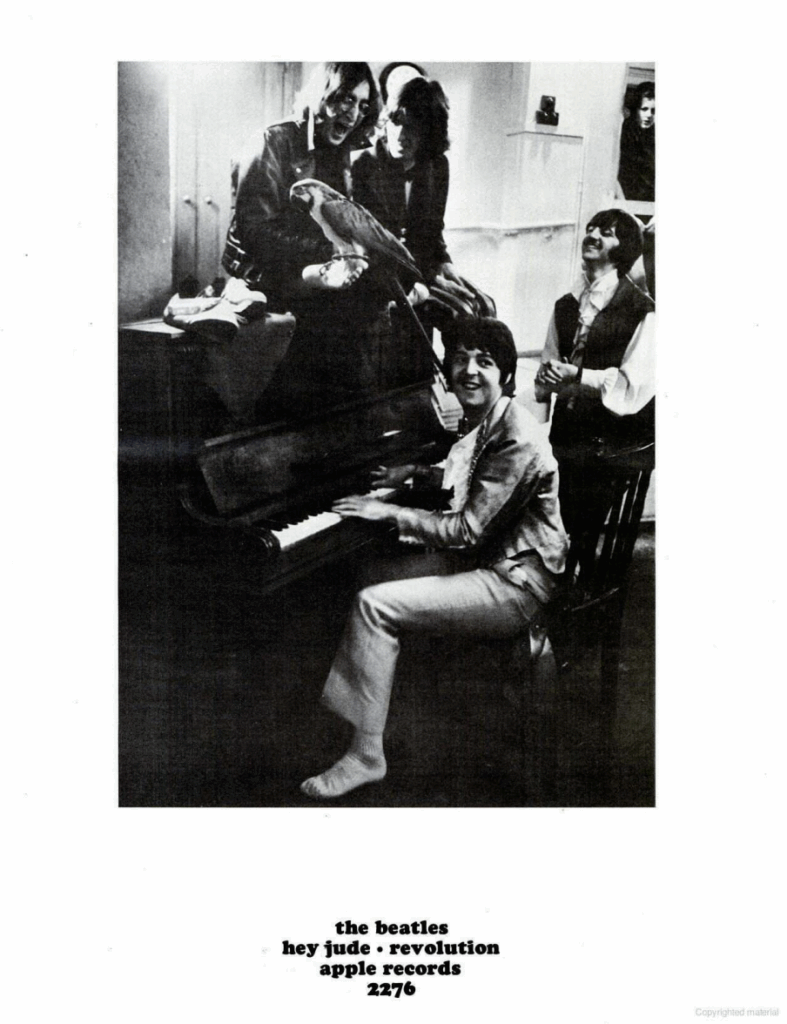

When “Hey Jude”/”Revolution” was released, Billboard stated, “Their first for their own label, distributed by Capitol, is a potent two-sided winner. First is an off -beat rhythm ballad with compelling lyric line while the flip is a solid rocker with another fascinating lyric.”

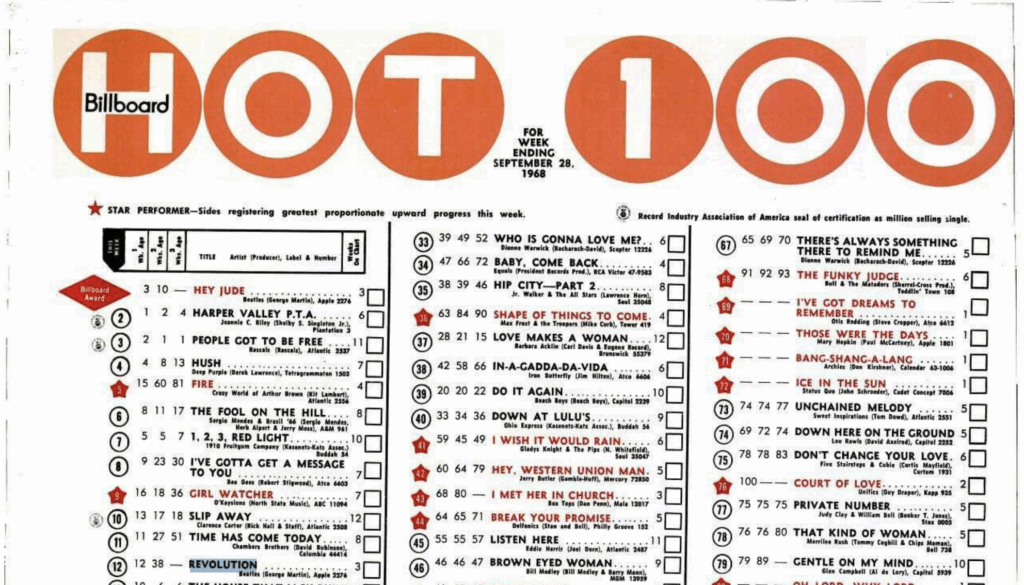

The Hey Jude”/”Revolution” single achieved massive commercial success, becoming one of the best-selling 45 records of all time with approximately 8 million copies sold. “Hey Jude” dominated the charts, claiming a nine-week run at number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, while “Revolution” reached number 12 as a B-side.

In a 1980 interview with Rolling Stone, Lennon reflected on how he describes “Beatle music,” noting, “It means a lot of things. There is not one thing that’s Beatle music. How can they talk about it like that? What is Beatle music? ‘Walrus’ or ‘Penny Lane’? Which? It’s too diverse: ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ or ‘Revolution Number Nine’?