What if the message in the song “Three Little Birds” by Bob Marley and the Wailers is true? Don’t worry about a thing, ’cause every little thing’s gonna be all right.

On September 18, 1980, Bob Marley sat down with Gil Noble for an interview on “Like It Is” at the Essex House hotel in Manhattan. He was in New York for the North American leg of the Uprising Tour and reflected on the question of “for a long time, things were kind of lean?”

“Well, yes, thing was kind of lean and scant, it leave to what is your expectation in how you do, you know. To me it was lean but I could stand it, because coming from the country where you learn to do things like, where you learn to depend on family and all of that. You go out and you plant your own corn and you watch the corn grow. When the corn grow you pick your own corn, you know what I mean? All of them fruits ‘pon them tree, you can get them,” said Marley.

“Well, when you in the city it’s a whole different ball game, you know?” said Marley. “People have to go to work, catch the bus. In the country all the day you go on the donkey and you ride the donkey to the farm and you cool, you know?… In the city people must catch the bus, go to work, get off work, come back home, you know? So it was a different thing up there.”

Bob Marley & the Wailers, along with backing vocalists The I-Threes—Bob’s wife Rita Marley, Marcia Griffiths, and Judy Mowatt—were early into the 35-date North American leg of the tour, which had already broken attendance records across Europe, most notably in Milan, where the crowd was estimated between 110,000 and 120,000 people.

The band performed at Madison Square Garden on September 19–20, opening for The Commodores in front of 20,000 people each night. The day after the final New York show, on September 21, Marley collapsed while jogging in Central Park. Rushed to the hospital, doctors delivered the news that the melanoma he’d been diagnosed with three years earlier had spread throughout his body. They advised him to stop touring immediately.

His bandmates urged him to stop performing, and wife Rita recalled, “I said to him, ‘You don’t have to do this, not in this condition,’ but Bob, his spirit was always stronger than his body.”

Two days later, he was scheduled to perform for a sold-out crowd of 3,500 at Pittsburgh’s Stanley Theatre.

On September 22, Pittsburgh promoter Rich Engler received a call from Marley’s booking agent. “There might be a problem,” said the agent. “Bob is not feeling very well. I don’t know what’s going on. I’ll keep you posted.”

The morning of the Pittsburgh show, Engler got another call from Marley’s booking agent. “They’re headed there, but I would be surprised if he plays.” Around 2 p.m., the band arrived for soundcheck. Engler found Marley in the dressing room, sitting on the couch. “I said, ‘I heard you’re not feeling well. I’m concerned. I hope you’re feeling better. Are you going to play?'” Engler recalled. “He said, ‘Mon, I wasn’t going to, but I’m going to for my band and everybody. It’s a sold-out show. I’m going to do it.'” According to Engler, Marley added, “The guys need the money.”

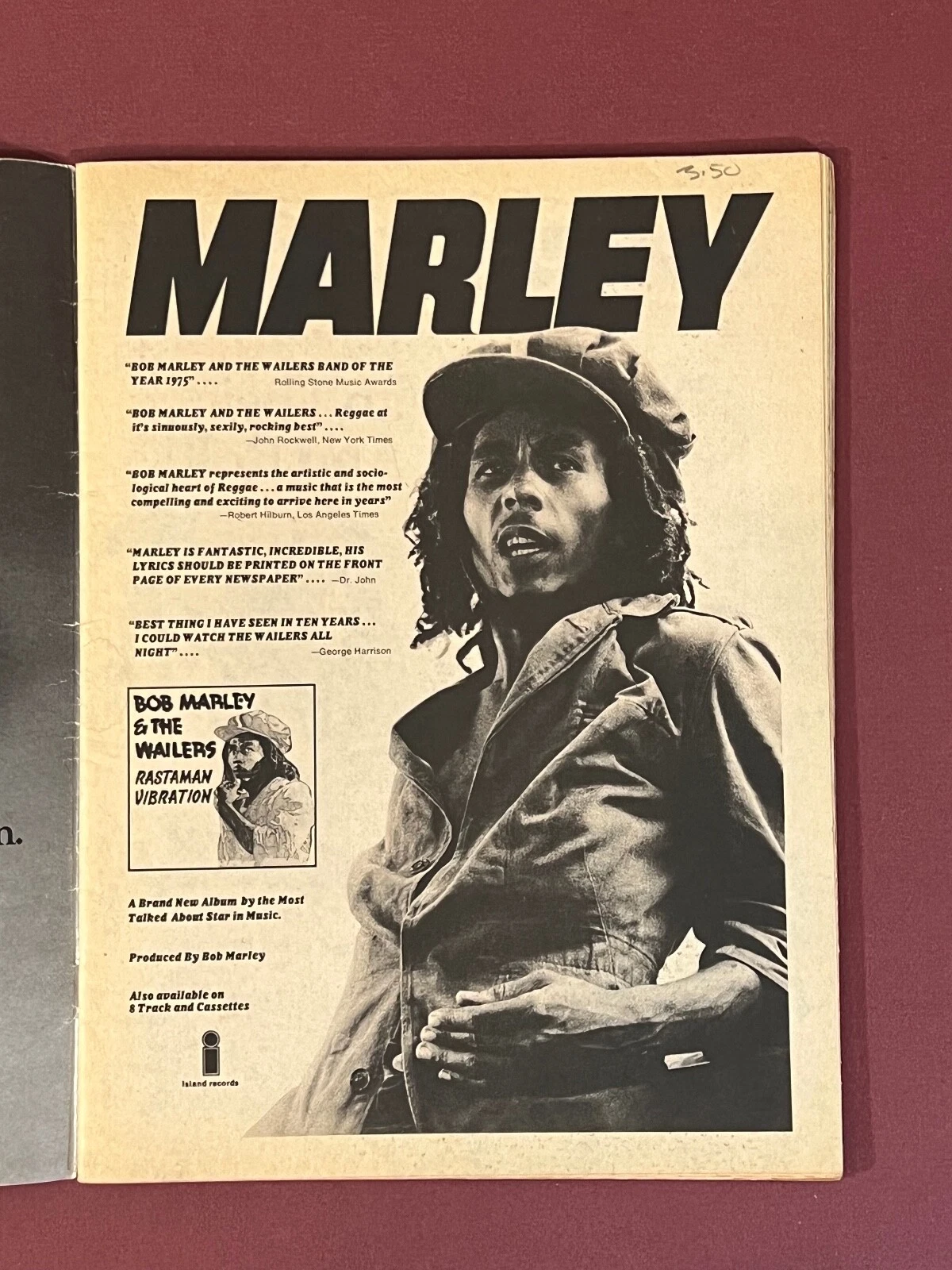

At that time, Marley was reggae’s leading ambassador but far from the legend he would become after his death eight months later at age 36. His only Top 10 album was 1976’s “Rastaman Vibration,” and none of his now-classic songs charted in the Top 40. To mainstream radio, he was still best known as the writer of “I Shot the Sheriff,” which Eric Clapton took to number one in 1974.

“His popularity was spotty. Songs like ‘Jammin’,’ it was pulling teeth to get the DJs to play them. They didn’t think it fit their format,” Engler said about Marley’s popularity in the United States. “It was a different form of rock for me, and it had its own movement. This concert sold out faster than any reggae concert we had done.”

Despite his illness, Marley took the stage that night for what would become his final performance, delivering a 20-song set that lasted nearly two hours, including two encores, ending with a 6:38 rendition of “Get Up, Stand Up.” The show was “magical,” said Engler.

Over the next eight months, Marley pursued treatment in New York and Germany. In May 1981, he decided to return to Jamaica. However, mid-flight over the Atlantic, his vital functions deteriorated, forcing the plane to make an emergency landing in Miami. There, at the Cedars of Lebanon Hospital on May 11, 1981, Bob Marley passed away.

Danny Sims heard the next Bob Dylan

Born in St. Ann Parish, Jamaica, on February 6, 1945, Robert Nesta Marley began recording music as a teenager in Kingston under the name Bob Marley. In 1963, Marley formed a vocal group with his childhood friend Neville Livingston, later known as Bunny Wailer, and Peter Tosh, who had moved to Trench Town from Westmoreland to join them. Bob and Bunny were raised together in the same West Kingston household because Marley’s mother and Bunny’s father lived as partners and had a daughter together, making the two boys stepbrothers.

The trio was mentored and influenced by singer Joe Higgs, who is widely recognized as the “Godfather of Reggae.” Higgs held music lessons in his yard in Trench Town, and the Wailers quickly became local celebrities, scoring a Jamaican number-one hit with “Simmer Down,” which reached the top of the Jamaican charts in February 1964.

“I structured the harmony. I am the one who taught The Wailers the craft, who taught them certain voice technique,” said Higgs.

Across the Atlantic, in 1964, Johnny Nash, an American R&B singer who would later achieve fame with “I Can See Clearly Now,” and his manager Danny Sims, a music producer and publisher, formed JoDa Records in New York. By 1965, Nash and Sims had relocated to Jamaica, drawn by affordable studio time, a rising music scene, and the need to escape pressure from the FBI. Two years later, Nash and Sims partnered with businessman Arthur Jenkins to launch JAD Records, naming it after their first initials: Johnny, Arthur, and Danny.

On January 7, 1967, Nash saw Marley sing at a Rastafarian grounation, an Ethiopian Christmas celebration, in Trench Town and was impressed with what he experienced. “Johnny told me about this fantastic artist,” said Sims. “He said the songs were great, and he had invited him up to see me at my house. Bob came up with Peter Tosh, and Rita, and Mortimer Planno.”

“What I heard,” Sim said, “was the next Bob Dylan.”

After hearing Marley sing, Sims signed the Wailers to both a publishing deal and a recording contract with JAD Records, and hired Marley and his bandmate Peter Tosh to write songs for Nash, including “Stir It Up.” However, JAD Records was unsuccessful in establishing them as performers in the United States.

“Reggae was not accepted as a commercial form at the time,” said David Simmons, Sims’s longtime business partner. “The world wasn’t ready for it.”

By 1972, after years of recording with limited commercial success beyond Jamaica, Marley caught the attention of Island Records founder Chris Blackwell and signed with the label. Blackwell was looking for a replacement for reggae artist Jimmy Cliff and felt it was time to “take the music out of Jamaica without taking Jamaica out of it.”

Blackwell recalled his first impression of the group, noting, “They were immediately something else, these three: strong characters. They did not walk in like losers, like they were defeated by being flat broke. To the contrary, they exuded power and self-possession. Bob especially had a certain something; he was small and slight but exceptionally good-looking and charismatic. Bunny and Pete had a cool, laid-back nonchalance.”

“As I took the measure of them, I thought, Fuck, this is the real thing. And their timing was good. Jimmy Cliff had just walked out on me a week earlier. Maybe it was kismet, I thought—just when Jimmy stormed out, Bob, Pete, and Bunny strolled in,” Blackwell said.

Blackwell wanted Bob Marley & The Wailers to be embedded into the rock music scene.

“I knew I could do something with them—move them away from where they were and make their music attractive to college kids who were otherwise ignorant of or indifferent to Black music,” said Blackwell. “They were shocked when I said that there was no way their music as it currently sounded would get played on US radio. This pissed them off, as if I were criticizing their music rather than noting the realities of the marketplace. It was just a fact. In that era, there were radio stations that played only rock music and R&B stations that played only Black music. And neither category of station played reggae.”

“I told them they needed to come over like a Black rock act, said Blackwell. “There were no precedents for this kind of thing in Jamaica, and barely anywhere else, except maybe in the US, which had Sly and the Family Stone. Being a ‘rock act,’ I told them, did not have to mean selling out or surrendering their identity. Pete and Bunny were skeptical, but Bob was immediately intrigued. Black Jamaican music was always evolving, from ska to rocksteady to reggae, and reggae was poised to evolve further.”

“I offered then and there to give them some money, asking them how much it would take to make an album, which was still rare in singles-driven Jamaica. They asked for much more than they actually needed to make an album, but it still wasn’t that much, £4,000. I said yes. I didn’t ask them to sign anything, which was a risk, but it seemed right in this instance. They had been so fucked over and had so many scores to settle that it seemed correct to do it this way,” said Blackwell.

This resulted in the album, “Catch a Fire,” which was released on April 13, 1973. It was a slow burn in terms of sales with about 6,000 copies in its first few months, and 14,000 within the first year. Blackwell recalled being extremely disappointed, while the label’s attitude was “That’s good for a reggae record.” His response: “Don’t think of it as a reggae record. It’s a rock record.”

Island put significant money and promotional muscle behind the album. In Britain, the Wailers played large venues, opening for Traffic and other Island acts. But in America, where reggae remained virtually unknown, Lee Jaffe, a 22-year-old aspiring filmmaker, artist, and musician who had befriended Marley, became the band’s road manager and booking agent. Jaffe secured the opening spot at Max’s Kansas City in New York on July 18–23, 1973, organizing what would become a historic event. Unknowingly, the band was set to open for the emerging Bruce Springsteen, who was then being promoted as the “new Bob Dylan.”

“It was exciting because it meant that for our purposes we wanted attention… radio wasn’t going to play us. That was the purpose of getting out there, and this was really great because everyone had to see this new act, Bruce Springsteen. Everyone in the media and Columbia was pushing it, and they were going to get everyone there who could possibly write about it or talk about it,” Jaffe recalled.

“The place only held like a hundred people, maybe not even, and I remember the first night there was like 10 people there for us, and then the second night it was like half full for us, and then by the third night it was packed. There was like a real buzz about the Wailers, this new group. Not only was it a new group, but it was music that people didn’t know about. It was a new genre of music, and it was very social, political. I think it was a really good look for Bruce to have the Wailers. It added something to the whole Bruce avalanche that was beginning,” said Jaffe. “It was smoky. It had the feeling that this was like an important cultural event, you know, this Jamaican group and the new Bob Dylan. It was exciting.”

The second album with Island, “Burnin’,” was released on October 19, 1973. But from the start of their partnership with Island Records, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer felt the dynamic shifting. Bunny, a fundamentalist Rasta, grew anxious about playing rock clubs and colleges, uncomfortable with the venues and struggling with the cold British weather and lack of vegetarian ital food. Marley embraced the opportunity.

“Soon enough, the Wailers became known as Bob Marley and the Wailers, not least because, although Tosh and Bunny were formidable talents and had great rebel presence, Bob had by far the most charisma and the most songs. He was clearly the leader—and, in a wider sense, transcending music, a leader. He was always hungry for experience and loved traveling and seeing other parts of the world,” Blackwell recalled.

By the mid-1970s, Tosh and Wailer had departed. The band retained its original rhythm section—drummer Carlton Barrett and bassist Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett—and added The I-Threes vocal trio: Bob’s wife Rita, Marcia Griffiths, and Judy Mowatt.

In the summer of 1975, Blackwell recorded Bob Marley and the Wailers performing live at the Lyceum Theatre in London. “I saw—and heard—the reaction of the audience to ‘No Woman, No Cry,’ and how they started chanting the chorus over the organ intro and The I-Threes even before Bob had started singing. This was quite a moment—the group hadn’t had a hit yet, but the crowd was out in force and already knew the Wailers’ songs inside out,” said Blackwell. “I kept telling my engineers, ‘Give me more audience!’ I wanted the home listener to hear the ecstatic roar and unison singing of that Lyceum crowd as Bob urged them on.”

The Lyceum recording established Marley as a growing force in Britain and Europe, with Catch a Fire and Burnin’ gaining airplay on rock and college radio stations. Island Records would leverage this momentum to bring reggae into the American market.

“I put my all into getting Bob’s music, and Jamaica’s music, into the mainstream,” said Blackwell.

The next album, “Rastaman Vibration,” in April 1976 became Marley’s first U.S. Top 10 album, reaching number eight on the Billboard charts with “Roots, Rock, Reggae” as the leading track.

In the June 17, 1976 issue of Rolling Stone, reviewer Robert Palmer stated, “Bob Marley has been writing moving songs, making vital and innovative music, struggling to the top in the anarchic Jamaican record business and slowly building an international following for almost ten years. Island Records has been trying to break him in the U.S. since the release of Catch a Fire, four albums ago, and the rock press has been pushing the albums, Marley and reggae music with a unanimous enthusiasm that makes even their efforts in Bruce Springsteen’s behalf seem equivocal. It’s working.”

Just as Marley was ascending, there was an assassination attempt on him. Around 9 p.m. on December 3, 1976, two days before the Smile Jamaica concert, bullets were fired at Marley’s house at 56 Hope Road. Ironically, the band was rehearsing “I Shot the Sheriff” upstairs. Marley was downstairs eating an orange when seven gunmen emerged from the doorway. Taylor, standing in front of Marley, took several shots to the leg and abdomen, likely saving Marley’s life. Marley was shot in the left arm, and a bullet grazed his chest. Outside, Rita Marley was shot in the head while trying to escape in her Volkswagen Beetle. Band member Louis Griffiths was shot twice in the stomach. Miraculously, no one died in the attempt.

Two days later, Marley performed a 90-minute set before 80,000 people at National Heroes Park. When asked why he performed so soon after being shot, Marley stated, “The people who are trying to make this world worse aren’t taking a day off. How can I?”

A newspaper review of the concert read, “A New York-based Jamaican who was at the event said that it reminded him of the famed Woodstock gathering which took place some years ago in upstate New York.” Performing that night, unable to play guitar due to the bullet still lodged in his arm, transformed Marley from musician into a symbol of resistance with unshakeable faith. At the end of the concert, Marley unbuttoned his shirt, and pointed to where he was shot in the chest and arm. As Marley left the stage, wife Rita on the microphone declared to the crowd, “Bob Marley, c’mon, sing it… Let him hear it. Praise it! C’mon people, the guy came out of his bed to sing for you tonight. Let him hear it.”

Marley went into exile for almost two years, first in the Bahamas at Blackwell’s Compass Point Studios as a recovery and writing retreat, then to England in February 1977 where he started to work on the “Exodus” album, with songs that included “Jamming,” “Waiting in Vain,” “One Love/People Get Ready,” and “Three Little Birds.”

“I met Bob in London on Valentine’s Day 1977. We started rehearsing right away. My first jam that day was ‘Exodus’, ‘Waiting In Vain’ and ‘Jamming’ – we played each song for about 45 minutes. Bob was still putting final touches to the lyrics and the music with the keyboard player, Tyrone Downie, who at the time was filling in on bass. Tyrone and myself helped write ‘Exodus’ and ‘Is This Love?’ It was a very electric experience. It was the first time I ever saw somebody’s aura. He was so happy to be alive after the shooting, smiling and having a good time. He was very comfortable in London. There was a great Jamaican and Afro-Caribbean community, people from Ethiopia, Africa,” said lead guitarist Junior Marvin.

“There was no rush in the studio, nobody watching the clock. We had it booked 24 hours a day; for Bob that was a dream come true. We had a good time recording live, the organic way. It would be drums, bass, piano, acoustic guitar, lead guitar, and rough vocals. Bob would redo his rhythm guitar, and a lot of the vocals,” said Marvin. “We spent a lot of time mixing, trying to perfect everything. We’d compare our album with the top albums of the time and see how ours measured up sonically. It wasn’t just great songs, but musically almost perfect. It really revolutionized the sound of reggae.” Rolling Stone ranks the album at number 48 on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

In early May 1977, just before the release of Exodus and its tour started, Marley injured his right big toe playing football (soccer) with French journalists in Paris.

“We played a match against some journalists in Paris that year, just walking distance from the hotel. Bob wasn’t playing in proper football boots, and a bredda tackled him. Bob’s toenail tore off as a result — not completely, but the nail was lifted up. So he stopped and told us to continue playing and went back to the hotel. I think it was hotel doctor who looked at it, and they clipped off the nail and bandaged it up,” said Neville Garrick, Marley’s art director and friend. “He had a black-and-blue bruise under his big toe. Not the whole toe — just the middle part. He never complained about it.”

Released on June 3, 1977, “Exodus” was the fifth studio album with Island Records. The album introduced reggae to mainstream audiences, peaking at number 20 on the Billboard 200 and number eight on the U.K. charts, where it remained for 56 consecutive weeks. Time magazine later called “Exodus” the best album of the 20th century, saying it “is a political and cultural nexus, drawing inspiration from the Third World and then giving voice to it the world over.”

The ongoing toe injury led to a medical examination that, in July 1977, revealed a rare form of skin cancer under the toenail. Doctors advised amputation, but Marley refused on religious grounds, choosing instead to have only the cancerous nail and tissue removed with a skin graft from his thigh. The impact was immediate as the final two shows in London were cancelled, and the entire U.S. leg of the Exodus Tour was first postponed and then entirely cancelled.

“We finished the tour and went back to America. We had planned to go into America with the Exodus tour, which had done well in Europe, and he went back to England to check up on the books, and also his toe. And that’s where doctors said they think he had cancer,” said Garrick. “I was with his mother when they called to tell her the news. And then the suggestion was, ‘Come to America for a second opinion.’ The suggestion was made that he may have to amputate the toe, but Rastaman wasn’t keen on that.”

On April 22, 1978, Marley returned to Jamaica for the first time since the failed assassination attempt to perform at the One Love Peace Concert at the National Stadium in Kingston. Known as “Third World Woodstock,” the event was attended by nearly 35,000 people and aimed to promote peace during Jamaica’s violent political conflict.

“I was 10,” recalled Marley’s son Ziggy. “It was a big crowd at the airport, and it was so crowded and hectic, they had to pull me through the car window to get me into the car. It was a very exciting time. It was like… like Jamaica was about to change.”

“It was, basically, ‘Bob is home!’ There was a whole heap of men in the yard — from both sides. Everybody come fi check Bob. We started working with the peace committee… there was press that came. International press, too,” said Garrick. “I remember one thing Bob tell them: ‘Rasta don’t go left, Rasta don’t go right — Rasta go straight ahead.’ It just [goes] to show you that Bob was drawing a line to say, ‘I’m behind the church, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church — not on any particular side.'”

The concert began at 5 p.m. and continued into the early morning hours of April 23, with Marley taking the stage around 12:30 a.m. as the closing act. Marley performed six songs before “Jammin’,” which is when rival political leaders Michael Manley and Edward Seaga were encouraged to come on stage.

“To show the people that you love them right, to show the people that you gonna unite, show the people that you’re over bright, show the people that everything is all right. Watch, watch, watch what you’re doing because I wanna send a message right out there. I mean, I’m not so good at talking, but I hope you understand what I’m trying to say. Well, I’m trying to say, could we have, could we have, up here onstage here the presence of Mr. Michael Manley and Mr. Edward Seaga. I just want to shake hands and show the people that we’re gonna make it right. We’re gonna unite, we’re gonna make it right, we’ve got to unite,” said Marley.

Manley and Seaga joined their hands together, with Marley in the middle holding them together. Unity, even for a brief moment, was experienced. The crowd celebrated, and Marley declared, “Love, prosperity be with us all. Jah Rastafari. Selassie I” and went into the final song, “Jah Live,” which is a spiritually uplifting song and means “God Is Alive.”

Survival was released on October 2, 1979, with anthems like “Zimbabwe” and “Africa Unite,” establishing Marley as pan-Africa’s spiritual voice. He was the only non-Zimbabwean artist invited to perform at Rufaro Stadium in Harare for Zimbabwe’s official Independence Day ceremonies. At midnight on April 18, 1980, as the new nation was born, some of the first official words spoken by the newly independent Zimbabwe were: “Ladies and Gentlemen, Bob Marley and The Wailers!”

Marley released his final studio album, Uprising, on June 10, 1980, featuring “Redemption Song” and “Could You Be Loved,” which debuted as the lead single and reached number 5 in the UK charts. By mid-1980, Marley had become a cultural icon for liberation movements around the world.

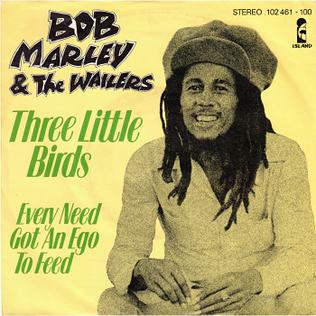

In August 1980, building on the success of “Could You Be Loved,” Island Records released “Three Little Birds” as a single, a feel-good song recorded three years earlier on the Exodus album. Two months later, in October 1980, “Redemption Song” was released as the final single before Marley’s death on May 11, 1981.

“The whole thing of Bob passing was just really a tragedy, a disgrace in a sense,” said Blackwell. “Nobody, absolutely nobody — from he himself, people close to him, to those who worked with him after that period, including myself — never mentioned anything to him about having regular checkups to see if there were any negative effects from the [soccer] accident he had on his toe. We did know that he was advised to have it amputated, and he didn’t want to do that because he loved soccer — 98 percent as much as he loved music. The thought that if he had his toe cut off he would no longer be able to play soccer in the same way, without the agility with his foot.”

“It’s a disgrace that all of us involved were not on him all the time to make sure he had checkups, and that really what happened,” said Blackwell. “Nobody did anything, and when it happened it was too late, had spread too much, and there was nothing that could be done.”

Lyrically: Three Little Birds by Bob Marley & the Wailers

In 1976, Bob Marley was inspired to write “Three Little Birds” while meditating in his backyard at Hope Road after a morning of football and prayer. According to his close friend and road manager, Tony “Gilly Dread” Gilbert, Bob immediately sent for pen and paper and began writing the lyrics as inspiration struck upon observing three canary birds visiting his windowsill. The song was then recorded in April 1977 during the Exodus album sessions shortly after the assassination attempt on him, and released on the album on June 3, 1977, then as a single on August 29, 1980.

“It was just amazing how he put the words for ‘Three Little Birds’ together in a flow,” said Gilbert. “Bob got inspired by many things around him. He observed life. I remember the three little birds. They were pretty birds, canaries, who would come by the windowsill at Hope Road.”

“Well, I have been around from then [when Bob Marley was alive], I know the entire family, including his mom… only his father I don’t know, but I know the entire family. I worked with Tuff Gong for about 16 years, and it’s been about seven to eight years since positioned at the museum,” said Ricky Chaplin, family friend and tour guide at the Bob Marley Museum in Kingston, Jamaica.

“This is the exactly spot Bob Marley stood and write, this is the exactly spot. Every morning, his duty is to get up very early, run, play football, and after that… that morning he sat right there and smoking his marijuana, meditating. And if he sat there smoking, before you make a spliff, you will make sure the herb is okay. So the seeds, you will pick them out. Sometime you throw them away, and if you throw away the seeds, sometimes birds come and pick the seeds up. And if you do that, it’s all the time he sat there and do that, so it will attract birds to know that this little Rastaman is going to come here and feed us. And then this song came into his mind, and he just wrote that beautiful song,” said Chaplin.

“I was performing for the weekend in New Kingston, and I invited sister Judy and Rita to come and do harmonies with me, and they were happy about it. And on the third night, we decided to do a jump session on stage, and the audience loved it, and they all encouraged us to form a group. And Bob immediately invited us in the studio to do… nothing… dream… the rest is history. We became his three little birds. Bobby’s a person who opened my eyes to realize that the music was not just entertainment and dancing and fun. It was much deeper. It’s such a positive vibration. You’re telling yourself, and you accept this message: don’t worry. So it’s like a rejuvenation. It’s spiritual medicine to the soul,” said Marcia Griffiths, a member of The I-Threes, Bob Marley’s backing vocal group.

Marcia Griffiths recalls, “After the song was written, Bob would always refer to us as the Three Little Birds. After a show, there would be an encore, sometimes people even wanted us to go back onstage four times. Bob would still want to go back and he would say, ‘What is my Three Little Birds saying?’ If we consent to go on again, then he will go.”

“‘Three Little Birds’ was our song, officially for I-Three. It was more or less expressing how we all came together, when he says, ‘Rise up this morning, smile with the rising sun.’ We loved it. Even when we were recording it, we knew that it was our song. Everybody knew that he was referring to us when he said ‘three little birds’—he never said four, or two. And then he would tell us that our lips are not for kissing, just for singing. We just laughed when he said that.”

Recording Engineer Terry Barham says that “Three Little Birds” was “taken from Jamaican reels” that were first recorded during the Rastaman Vibration time in early 1976. “I’m pretty sure… ’cause I can remember most things and that song was already there when the London sessions began,” said Barham. “You know that high synth sound? We didn’t have anything in London that was capable of making it.”

The song and its simple message make it feel as if Bob Marley is speaking directly to you when he sings, mainly because the lyrics have quotes around them.

“Don’t worry about a thing,

‘Cause every little thing gonna be alright.

Singing’ “Don’t worry about a thing,

‘Cause every little thing gonna be alright!”

While “Get Up, Stand Up,” “I Shot the Sheriff,” and “War” were highly influential in spreading a call to action to the masses, “Three Little Birds” patiently flew in at the correct time, reminding the world through all the chaos that every little thing, even when they add up, will be alright. Worry is not productive, and we should smile, pure and true, and be grateful for this new day.

Rise up this mornin’,

Smiled with the risin’ sun,

Three little birds

Each by my doorstep

Singin’ sweet songs

Of melodies pure and true,

Saying’, (“This is my message to you”)

“You just can’t live that negative way. You know what I mean. Make way for the positive day. Cause it’s a new day,” said Marley. “Life and Jah are one in the same. Jah is the gift of existence.”

Blackwell said, “I always loved ‘Three Little Birds.’ I thought it was just so light, very poppy, and I thought Bob got away with it fine.”

“Yes, the whole thing was really, really positive, from beginning to end. You know, every time you mention a track, I just know more and more that Exodus is really a special album,” said Griffiths about the song and the album. “Ordained by God, written by the hand of God himself.”

Saying’, (“This is my message to you”)

Singing’ “Don’t worry ’bout a thing,

‘Cause every little thing gonna be alright.”