Bruce Springsteen was not always “the Boss.”

In the 1950s, the Springsteen family struggled to make ends meet in Freehold, New Jersey. As Springsteen later recalled, “We were pretty near poor, though I never thought about it. We were clothed, fed and bedded.”

Bruce’s father, Douglas, held various jobs, working at Ford, Nescafe, a local plastics factory, and driving trucks, buses, and taxis, while his mother, Adele, worked as a legal secretary and provided most of the family’s income. During his earliest years, the family lived with his grandparents, along with his younger sister Virginia.

“My mother was bright, happy, she’d merrily make conversation with a broom handle, she believed that there was good faith, good heart, good hope in all citizens. She gave the world a lot more credit perhaps than it deserves, but that was her way,” said Springsteen. “My mother was someone who pressed every day to make herself visible, to present herself, and to have impact upon even the limited world that she was a part of. And she took great pride in that… She was a very, very inspirational presence. A source of a lot of my own ideas about the way to go about approaching my job and the kind of combination of seriousness and joyfulness.”

“My father felt his invisibility very extremely, very intensely,” said Springsteen. “Work is such a big part of people’s lives. If you feel like things are sailing away from you and you’re left standing on the dock, I think you end up living in the shadow of a dream. I think that’s how my dad felt a lot of times.”

“I’d seen gods turn into devils at home. I’d witnessed what I felt was surely the possessive face of Satan. It was my poor old pop tearing up the house in an alcohol-fueled rage in the dead of night, scaring the shit out of all of us. I’d felt this darkness’s final force come visit in the shape of my struggling dad . . . physical threat, emotional chaos and the power to not love,” recalled Springsteen. It was later revealed that his father suffered from undiagnosed paranoid schizophrenia.

“Our house was old and soon to be noticeably decrepit. One kerosene stove in the living room was all we had to heat the whole place. Upstairs, where my family slept, you woke on winter mornings with your breath visible. One of my earliest childhood memories is the smell of kerosene and my grandfather standing there filling the spout in the rear of the stove,” said Springsteen. “We had a small box refrigerator and one of the first televisions in town.”

On this TV in 1956, when Springsteen was 6 years old, he experienced a “big bang” in his world when Elvis Presley appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show. Describing this moment, he said it was from “ANOTHER WORLD… the one below your waist and above your heart… A world that had been previously and rigorously denied was being PROVEN TO EXIST!”

He was inspired to take up music and get himself a guitar. “The next day I convinced my mom to take me to Diehl’s Music on South Street in Freehold. There, with no money to spend, we rented a guitar. I took it home. Opened its case. Smelled its wood, felt its magic, sensed its hidden power. I held it in my arms, ran my fingers over its strings, held the real tortoiseshell guitar pick in between my teeth, tasted it, took a few weeks of music lessons . . . and quit,” said Springsteen. “It was TOO FUCKIN’ HARD! Mike Diehl, guitarist and owner of Diehl’s Music, didn’t have any idea how to teach whatever Elvis was doing to a young shouter who wanted to sing the elementary school blues.”

As a student, Springsteen never felt like he fit in, stating, “I was invisible in school. Wasn’t even the class clown. I had nowhere near that much notoriety.”

“Now on school mornings… so of course I hated getting up and uh, my mom had perfected this technique in the morning where she’d stand over my bed with a glass of ice water and give me 30 seconds, eh you know, ‘Five, four, three, two’, boom! Niagara Falls. I would get dressed, I would drift downstairs to breakfast where I would feast daily on a huge bowl of sugar pops… with a buzz on, and a kiss from my mom, I was off, with my sister, lumbering up the street with our book bags, as my mom’s high heels clicked lightly in the other direction toward Lawyer’s Title Insurance Company.”

In 1962, the family welcomed his younger sister Pamela to the world. Two years later, in 1964, at age 14, Springsteen was driving with his mom, listening to the radio, when “I Want to Hold Your Hand” by the Beatles engulfed him over the airwaves. It was the year Beatlemania swept America, forever changing music and Bruce Springsteen.

“This was another song that changed the course of my life. It was a very raucous sounding record when it came out of the radio. It really was the song that inspired me to play rock and roll music — to get a small band and start doing some small gigs around town. It was life-changing,” said Springsteen. “That was going to change my life because I was going to successfully pick the guitar up and learn how to play.”

Inspired once again, he faced a roadblock.

“My parents had no money for a second shot at the guitar, so there was just one thing to do: get a job. One summer afternoon my mom took me to my aunt Dora’s, where for fifty cents an hour I would become the ‘lawn boy.’ My uncle Warren came out and showed me the ropes. He demonstrated how the lawn mower worked, how to cut the hedges, and I was hired. I went immediately to the Western Auto store, an establishment in the town’s center specializing in automotive parts and cheap guitars. There amongst the carburetors, air filters and fan belts hung four acoustic guitars, ranging from the unplayable to the barely playable. They looked like nirvana to me and they were attainable. Well, one was attainable. I saw a price tag hanging off of one funky brown model that read ‘Eighteen dollars.’ Eighteen dollars?”

By mid-summer 1964, Springsteen had earned enough money from lawn care and painting a neighbor’s house that he could finally afford his guitar. “It was done. Me and my twenty dollars went straight downtown. The salesman pulled my ugly brown dream out of the window and snipped off the price tag, and it was mine. I skulked home with it, not wanting my neighbors to know of my vain and unrealistic ambitions. I hauled it up to my bedroom and closed the door like it was some sex tool (it was!). I sat down, held it in my lap and was utterly confused. I had no clue about how to begin,” said Springsteen. “I stood up, went to the mirror on the back of my bedroom door, slung the guitar across my hips and stood there.”

“The first day I can remember looking in a mirror and being able to stand what I was seeing was the day I had a guitar in my hand,” said Springsteen.

“Bob Dylan is the father of my country”

“For me, my education was those records. That was it. There’s more to life than what you see around. And that was something that they couldn’t teach me in school. You couldn’t learn it from people you were hanging with out on the street or anything. You know, just, that was the most important lesson of my life,” said Springsteen.

Music gave Bruce Springsteen an identity, stating it was something that “provided me with a community, filled with people, and brothers and sisters who I didn’t know, but who I knew were out there. We had this enormous thing in common, this ‘thing’ that initially felt like a secret…a home where my spirit could wander… Music gave me something. I was running through a maze. It was never just a hobby. It was a reason to live.”

“Five months later, I’d beaten my Western Auto special half to death. My fingers were strong and callused. My fingertips were as hard as an armadillo’s shell. I was ready to move up. I had to go electric. I explained to my mother that to get in a band, to make a buck, to get anywhere, I needed an electric guitar. Once again, that would cost money we didn’t have. Eighteen dollars wasn’t going to cut it this time,” said Springsteen. “If I’d sell the pool table, she’d try to come up with the balance for an electric guitar I’d spotted in the window of Caiazzo’s Music Store on Center Street. The price was sixty-nine dollars and it came complete with a small amplifier. It was the cheapest they had but it was a start.”

Springsteen sold his pool table for $35, and on Christmas Eve, he and his mother bought a Kent guitar. “It looked beautiful, wondrous and affordable. I had my thirty-five dollars and my mother had thirty-five dollars of finance-company money… Sixty-nine dollars would be the biggest expenditure of my life and my mother was going out on a limb for me one more time… In the living room I plugged in my new amp. Its tiny six-inch speaker ‘roared’ to life. It sounded awful, distorted beyond all recognition. The amp had one control, a volume knob. It was about the size of a large bread box but I was in the game.”

Springsteen was influenced by Elvis and the Beatles, and connected with artists like Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Buddy Holly, Roy Orbison, and Duane Eddy through radio and records. However, it was in 1965, at age 15, when Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” came on the radio and his life changed once again.

“The first time that I heard Bob Dylan I was in the car with my mother… and on came that snare shot that sounded like somebody kicked open the door to your mind from ‘Like a Rolling Stone.’ I knew that I was listening to the toughest voice that I had ever heard. It was lean and it sounded somehow simultaneously young and adult, and I ran out and I bought the single,” said Springsteen. “Then I went out and I got Highway 61 and it was all I played for weeks. Looked at the cover with Bob with that satiny blue jacket and the Triumph motorcycle shirt. And when I was a kid, Bob’s voice somehow—it thrilled and scared me. It made me feel kind of irresponsibly innocent, and it still does. But it reached down and touched what little worldliness I think a 15-year-old kid in high school in New Jersey had in him at the time. Dylan, he was a revolutionary. The way that Elvis freed your body, Bob freed your mind. And he showed us that just because the music was innately physical did not mean that it was anti-intellect. He had the vision and the talent to expand the pop song until it could contain the whole world. He invented a new way a pop singer could sound. He broke through the limitations of what a recording artist could achieve, and he changed the face of rock and roll forever.”

To Springsteen, “Bob Dylan is the father of my country… He inspired me and gave me hope. He asked the questions everyone else was too frightened to ask, especially to a fifteen-year-old: ‘How does it feel… to be on your own?’ A seismic gap had opened up between generations and you suddenly felt orphaned, abandoned amid the flow of history, your compass spinning, internally homeless. Bob pointed true north and served as a beacon to assist you in making your way through the new wilderness America had become.”

His guitar, and the music around him, saved Springsteen from being invisible.

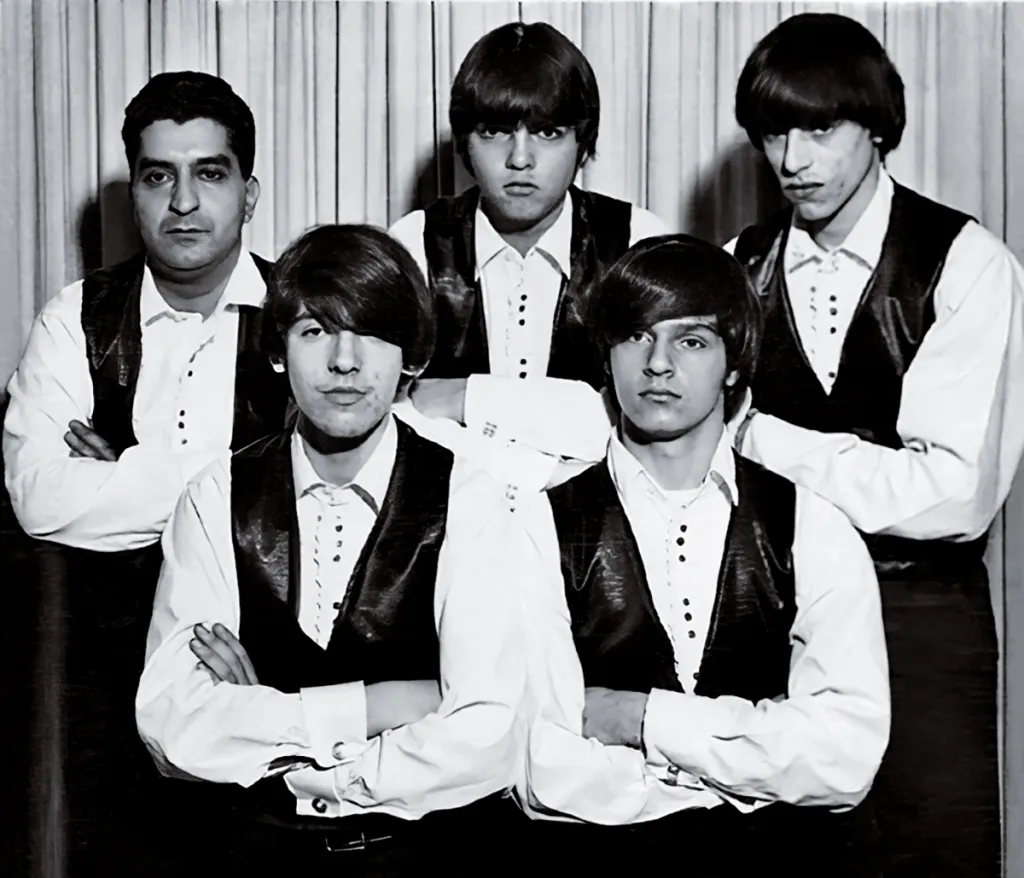

In 1965, at age 16, he auditioned and joined his first real band, The Castiles.

“One summer afternoon I heard a knock on my front door and it was George Theiss, a school pal of mine who was dating my sister, and I figured he was coming to see her. But instead, she had told him that I played the guitar, which I had for about six months, and he said he wanted me to come over and audition for his band,” said Springsteen. “So that weekend I followed him to a part of town where the rug mill was and in a little shotgun shack they cleared out a tiny little dining room and there was some band equipment set up. And it was there in that little room, no bigger than this little spot I’m standing on, that I embarked on the greatest adventure of my life. I joined my first real rock and roll band and we lasted for three years, which is an incredibly long time for teenagers to stay at one place: 1965, 1966, 1967. We played all up and down the Jersey Shore and we played Ranch Village. It was an explosive time in American history. It was an incredible period of time to be in a rock and roll band, and we named ourselves after a bottle of shampoo.”

Theiss and Springsteen joined up with the original Castiles lineup consisting of Paul Popkin on guitar and vocals, Frank Marziotti on bass, and Bart Haynes on drums. Haynes later enlisted in the Marine Corps and was sent to Vietnam, where he was killed in action. Vinny Maniello took over on drums while Bart was serving.

The band performed cover songs at junior high school dances, roller rinks, drive-in theaters, supermarket openings, and clubs throughout New Jersey and New York, decked out in white pants, Beatle boots, and Beatle haircuts. The rehearsal space was given to the band by friends of Theiss, Gordon “Tex” Vinyard and his wife Marion. Tex became their manager, while Marion served as what Springsteen described as the band’s “house mother.” The Vinyards supplied meals, purchased guitar strings, and helped acquire equipment.

On May 18, 1966, Tex helped arrange a studio session at “Mr. Music Inc” in Bricktown, New Jersey. Springsteen and Theiss co-wrote two original songs in Vinyard’s car on the way to the session: “Baby I” and “That’s What You Get.” These became The Castiles’ first and only studio recordings. “It was a big deal,” recalled Springsteen. “Cuz it was the first time you heard yourself coming back on tape.”

Over three years and more than 115 performances, The Castiles helped develop Springsteen into a capable guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter. However, The Castiles eventually disbanded and Springsteen continued with his musical journey and briefly performed with Earth, a band of local college students.

Then, on February 14, 1969, drummer Vini Lopez saw Springsteen’s performance with Earth and invited him to form a new band. Just over a week later, on February 23, 1969, at the Upstage Club in Asbury Park, New Jersey, “Child” was officially formed. The original lineup included Bruce Springsteen on guitars and vocals, Vini Lopez on drums, Danny Federici on keyboards, and Vinnie Roslin on bass.

The Vietnam War was intensifying, and so was the tension in Springsteen’s home life, particularly between him and his father.

“There wasn’t any kind of political consciousness down in Freehold in the late Sixties. It was a small town, and the war just seemed very distant. I mean, I was aware of it through some friends that went,” said Springsteen. “When I was nineteen, I wasn’t ready to be that generous with my life. I had tried to go to college, and I didn’t really fit in. I went to a real narrow-minded school where people gave me a lot of trouble and I was hounded off the campus—I just looked different and acted different, so I left school.”

SSpringsteen had grown long hair and a rebellious spirit. “My father, he was in World War II, and he was the type that was always sayin’, ‘Wait till the army gets you. Man, they’re gonna get that hair off of you. I can’t wait. They gonna make a man outta you.’ We were really goin’ at each other in those days,” recalled Springsteen.

On August 19, 1969, Springsteen received a 4-F classification, making him ineligible for service due to a brain concussion from a motorcycle accident when he was seventeen. When he returned home and told his parents, his father’s response surprised him. “My father sat there, and he didn’t look at me, he just looked straight ahead. And he said, ‘That’s good,'” recalled Springsteen.

Child soon became Steel Mill when guitarist Robbin Thompson joined. They discovered another group had already registered the name “Child,” forcing the change. During this period, Steel Mill became a fixture at the Upstage Club in Asbury Park, where Springsteen’s friend Steven Van Zandt, a guitarist and vocalist, was also a regular performer. Van Zandt eventually joined Steel Mill, and the two formed a friendship that would define both their careers.

Steel Mill proved to be Springsteen’s most important band yet, building a following on the Jersey Shore while opening for major acts like Chicago, Roy Orbison, Ike & Tina Turner, and Black Sabbath. Steel Mill started to play across the country, including in Virginia, and eventually made it to California, where the Fillmore West held auditions every Tuesday.

“We nailed down a Tuesday slot and, nerves a-jingle-jangle, we headed down to stand on that stage and make our mark. You were one of five or six bands that would play for an hour or so to a paying crowd seated on the floor. Everybody there was good—you had to be to simply get an audition—but I didn’t see anybody very exciting. Many simply droned on, playing in that very laid-back San Francisco style. When the workingmen from New Jersey took the stage, all that changed. We rocked hard, performing our physically explosive stage show, which had the crowd on its feet and shouting. We left to a standing ovation and some newfound respect, and were asked back for the following Tuesday,” said Springsteen.

“We went home satisfied, counting the days ’til the following Tuesday. We came back one week later and did it one more time to the same tumultuous response, then were offered a demo recording session at Bill Graham’s Fillmore studios. Finally, just what we’d come three thousand miles for: our shot at the gold ring,” said Springsteen.

“One crisp California afternoon, Steel Mill pulled up to the first professional recording studio we’d ever seen,” recalled Springsteen. “We cut three of our best originals, ‘The Judge Song,’ ‘Going Back to Georgia’ and ‘The Train Song,’ as a demo for Bill Graham’s Fillmore Records… The demo was as far as we’d get. The deal never happened. We were offered some sort of retainer fee but nothing that showed any real interest.”

Steel Mill’s final performance was on January 23, 1971, and the band disbanded, but Springsteen said, “I learned. I went some place I hadn’t been. I went into a bigger environment musically, and I learned that we were very good, but not quite as good as I thought we were. I had to think what I was going to do about that.”

“Play me something”

Following Steel Mill’s disbandment and his brief experiments with bands called Dr. Zoom and the Sonic Boom and the Bruce Springsteen Band, Springsteen’s trajectory changed dramatically. In the fall of 1971, friend Carl “Tinker” West introduced Springsteen to Mike Appel, a songwriter and producer who had written for major acts like the Partridge Family.

“Bruce Springsteen, when he first walked into our offices, it was November ’71. He played two songs, he sat down at piano bench… he came up with a fellow by name of ‘Tinker’ who was a friend,” said Appel. “After the two songs, they were lyrically nothing to write Mother about. He sang them within great intensity. In fact, the intensity was almost too much for the value of the song. But he was better than the song. And so when he finished them, he said, ‘Well, that’s it.’ And I said, ‘Well, you know, that’s not going to be enough. I mean, you’re going to have to do better songs than this.’ And he said, ‘No, don’t worry. I’ve got plenty of songs, and I’ll have more songs.'”

Appel suggested he work on new material and come back when he’s ready because he saw something in Springsteen. “I also had the confusion of hearing a voice in my own head say, ‘This kid’s a superstar’,” said Appel.

Springsteen came back to see Appel two months later in February with more songs.

“He comes up and he starts playing songs. First song he played blew me right out the door,” said Appel. “It was ‘If I Was the Priest.’ And then ‘Does This Bus Stop’ and ‘Saint in the City.’ And it was like, ‘My God.’ He sang maybe, I don’t know, maybe five or six songs all together.”

“It seemed like this was someone who saw value in me, and he was connected to the music business. This was sort of as close to the real music business as I’d ever seen,” said Springsteen.

Springsteen signed a management contract with Appel and started to secure auditions.

“Our first audition was at Atlantic Records. All I remember is going up to an office and playing for somebody. No interest. The next thing Mike finagled—and I couldn’t believe it—was an audition with John Hammond. John Hammond! The legendary producer who signed Dylan, Aretha, Billie Holiday—a giant in the recording business. I’d just finished reading the Anthony Scaduto Dylan biography and I was going to meet the man who made it happen!,” said Springsteen.

On May 2, 1972, at the office of John Hammond at Columbia Records in New York City, Springsteen, about to perform, said to himself, “I’ve got nothing, so I’ve got nothing to lose. I can only gain should this work out. If it don’t, I still got what I came in with.”

“Poised and ready to hate us,” said Springsteen. “But he just leaned back, slipped his hands together behind his head and, smiling, said, ‘Play me something.’ I sat directly across from him and played ‘Saint in the City.’ When I was done I looked up. That smile was still there and I heard him say, ‘You’ve got to be on Columbia Records.’ One song—that’s what it took. I felt my heart rise up inside me, mysterious particles dancing underneath my skin and faraway stars lighting up my nerve endings.”

“That was wonderful, play me something else,” said Hammond. Springsteen played “Growin’ Up,” “Mary Queen of Arkansas,” and “If I Was the Priest.” Impressed, Hammond knew that Clive Davis, Columbia Records’ president, had final approval on all signings. He gave Springsteen guidance for the Davis audition, then asked to see him perform live that same night. Springsteen found an open time between eight o’clock and eight-thirty at Max’s Kansas City. Hammond came, experienced Bruce Springsteen live. “John was beaming. I could perform,” Springsteen said.

“Things started to happen…slowly. A few weeks after I met John, he ushered me into Clive Davis’s office, where I was warmly welcomed. I played Clive a few songs and with gentle fanfare, I was invited to join the Columbia Records family.”

While Appel compared Springsteen as “the new Bob Dylan,” Davis stated, “I saw him as a real original, someone who was not just the new Bob Dylan or another Bob Dylan, that was the kiss of death in those days. And so, I was excited and I signed him.”

At the age of 22, Springsteen signed a deal with Columbia.

“I didn’t have a chance to even call other labels and try to get him into a bidding war. It was like so fast. I mean… I wasn’t gonna attempt the gods when Columbia Records calls and you got both Clive Davis, both John Hammond on your side, you want to make a deal. You’re not going to be petulant and cute, right? So we did, and it was great,” said Appel.

“I saw rock and roll future”

Following his Columbia deal, Springsteen started to craft his debut album.

“I got back and for the first time in my life I stopped playing with a band and concentrated on songwriting. At night in my bedroom with my guitar and on an old Aeolian spinet piano parked in the rear of the beauty salon, I began to write the music that would comprise Greetings from Asbury Park,” said Springsteen.

By October 1972 he was at 914 Sound Studios in Blauvelt, New York, recording what would become Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.

“We cut the whole record in three weeks. Most of the songs were twisted autobiographies. “Growin’ Up,” “Does This Bus Stop,” “For You,” “Lost in the Flood” and “Saint in the City” found their seed in people, places, hangouts and incidents I’d seen and things I’d lived. I wrote impressionistically and changed names to protect the guilty. I worked to find something that was identifiably mine,” said Springsteen.

“We turned it in and Clive Davis handed it back saying there were ‘no hits,’ ‘nothing that could be played on the radio’,” recalled Springsteen. “I went to the beach and wrote “Spirit in the Night,” came home, busted out my rhyming dictionary and wrote “Blinded by the Light,” two of the best things on the record.”

There was a mix of solo acoustic and full band songs featuring drummer Vini “Mad Dog” Lopez, keyboardist David Sancious, bassist Garry Tallent, saxophonist Clarence Clemons, and organist Danny Federici. This crew of musicians would form the core of the E Street Band when it officially came together later in October.

Released on January 5, 1973, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. was received with mixed reviews and slow sales.

“Bruce makes a point of letting us know that he’s from one of the scuzziest, most useless and plain uninteresting sections of Jersey. He’s been influenced a lot by the Band, his arrangements tend to take on a Van Morrison tinge every now and then, and he sort of catarrh-mumbles his ditties in a disgruntled mushmouth sorta like Robbie Robertson on Quaaludes with Dylan barfing down his neck. It’s a tuff combination, but it’s only the beginning,” said Lester Bangs of Rolling Stone. “Bruce Springsteen is a bold new talent with more than a mouthful to say, and one look at the pic on the back will tell you he’s got the glam to go places in this Gollywoodlawn world to boot. Watch for him.”

“If ‘Greetings From Asbury Park, NJ.’ had borne the name Bob Dylan instead of that of Bruce Springsteen, what would the reviews have been like? I’ll tell you. They’d have raved,” read the album review by Ian MacDonald in the New Musical Express. “If this is really where we’re at, we’re in trouble.”

Springsteen had officially been dubbed the “New Bob Dylan,” a label that would stick with him through his early career, even as he worked to establish his own identity. Springsteen said sales of the album at first “sold about twenty-three thousand copies; that was a flop by record company standards but a smash by mine.”

Springsteen and the E Street Band went on tour. The first official gig was a free show at a Pennsylvania college opening for Cheech and Chong. “I came out, and we played about five songs. I thought it was going really good, I was sitting at the piano and someone tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘That’s enough’,” remembers Springsteen.

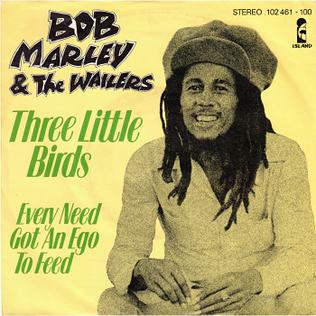

“We drove, we played, we drove, we played, we drove, we played. We opened for Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Sha Na Na, Brownsville Station, the Persuasions, Jackson Browne, the Chambers Brothers, the Eagles, Mountain, Black Oak Arkansas. We shared bills with NRBQ and Lou Reed and did a thirteen-day arena tour with brass-section hit makers Chicago,” said Springsteen. “We were top billed, with Bob Marley and the Wailers opening (on their first US tour), in the tiny 150-seat Max’s Kansas City. On stages across America we were cheered, were occasionally booed, dodged Frisbees from the audience, received rave reviews and were trashed.”

It was on this stretch of shows that Springsteen acquired the nickname “the Boss” because he collected the band’s nightly pay and distributed it.

Springsteen was under contract to Columbia for a new album every six months and the pressure was on record. His second album, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, took three months to record at 914 Studios and was released on November 5, 1973. The album was again not well received with “few even knew it had been released,” with those who did hear it say, “The songs are too long.”

Tensions between Columbia and Springsteen were heightened as his music was not translating into sales, with talks that the label would drop him.

“I was trying to come up with the first song in my new record, you know. I had two records out, they hadn’t done that well, and I had only had a three record deal, so this is my last shot, right? So I was going to have to give it everything I had,” said Springsteen. “It was definitely make or break at the time… I wasn’t very held in very low esteem at my record company. The guys signed me had all gone and moved and moved to other places, so I wasn’t a feather in anybody’s cap. If I was successful it didn’t matter, so I was really kind of at the bottom of their of their barrel.”

John Hammond retired from Columbia, and Clive Davis was fired from Columbia Records in May 1973, right after Springsteen’s first album came out.

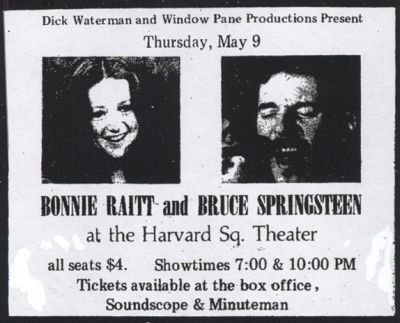

On May 9, 1974, Springsteen opened for Bonnie Raitt at the Harvard Square Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Unknowingly, this night would change everything.

In the audience was the rock reporter and founder of Creem Magazine. Jon Landau, an influential music critic for Rolling Stone and the Real Paper was . His review declared he had experienced the future of rock.

“I saw my rock’n’roll past flash before my eyes. And I saw something else: I saw rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen. And on a night when I needed to feel young, he made me feel like I was hearing music for the very first time,” said Landau. “When his two-hour set ended I could only think, can anyone really be this good; can anyone say this much to me, can rock’n’roll still speak with this kind of power and glory? And then I felt the sores on my thighs where I had been pounding my hands in time for the entire concert and knew that the answer was yes.”

“Springsteen does it all. He is a rock’n’roll punk, a Latin street poet, a ballet dancer, an actor, a joker, bar band leader, hot-shit rhythm guitar player, extraordinary singer, and a truly great rock’n’roll composer,” wrote Landau.

Some songs Springsteen played were “The ‘E’ Street Shuffle,” “New York City Serenade,” “Rosalita,” and what may have been the first-ever performance of “Born to Run.”

In October 1974, Springsteen returned to Boston to play the Music Hall. After the show, he and Landau talked about Springsteen’s future. Two albums had come and gone with little commercial success. Landau saw Springsteen’s raw talent wasn’t translating to professional recordings. He joined the team as co-producer alongside Mike Appel, pushed to move sessions to better studios, and helped Springsteen capture on tape what he delivered on stage. The result was Born to Run.

On August 25, 1975, Springsteen released the album Born to Run, which he described as sounding like “Roy Orbison singing Bob Dylan, produced by Spector.”

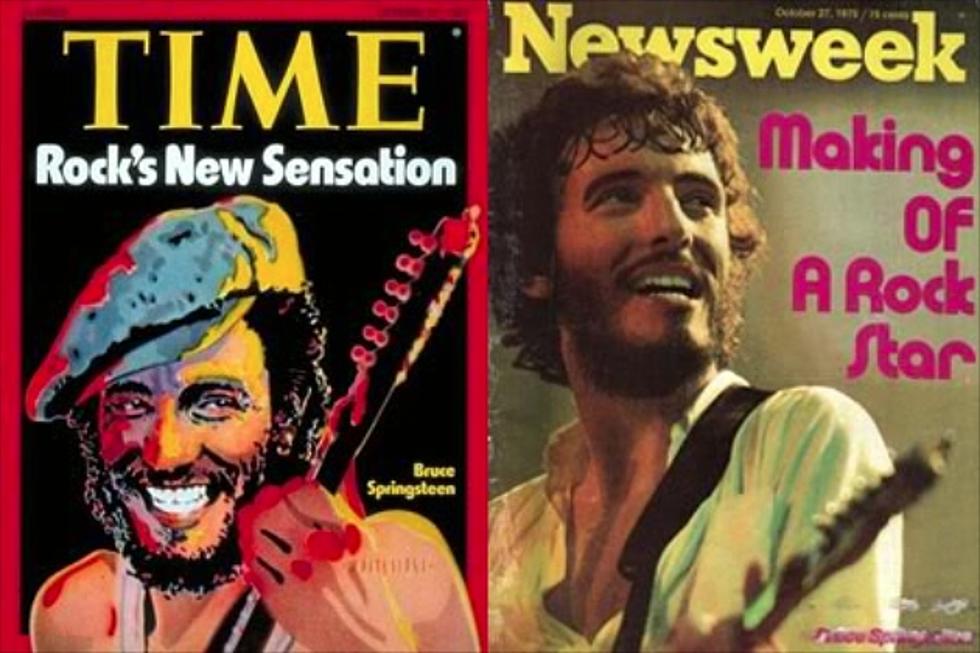

By October, Springsteen became the first entertainer to grace the covers of both Time and Newsweek in the same week. “I spoke to my dad. I was going to be on the cover of Time and Newsweek, and it’s a problem. Me, the cover of Time and Newsweek, which was like saying, ‘Yeah, I’m taking Santa Claus’s job at the North Pole this year,’ you know? I mean, it was just as fantastical, you know?” said Springsteen. “Well, he says, you know, ‘Better you than another picture of the president.'”

The album and its title track became an anthem. “Born to Run” reached the American Top Ten, which was a first for Springsteen. More importantly, it freed him from the burden of being the “New Bob Dylan.” He was now known and respected as Bruce Springsteen.

The Boss of the USA

After Born to Run became a massive hit in 1975, Springsteen faced a legal battle with his former manager Mike Appel over contracts he had signed without legal counsel years earlier. The dispute prevented him from entering a recording studio for nearly three years, but he kept touring and continued to build a following from his live performances. The legal dispute ended in May 1977 with a settlement that gave Springsteen control over his music and career and freed him to record again.

Springsteen released Darkness on the Edge of Town in June 1978, a harder rock sound than Born to Run. It reached #5 on the Billboard 200.

In 1980, Springsteen traded in his black leather jacket from the Born to Run era for a sport coat and tucked-in dress shirt, and released The River, a double album that became his first #1 on the Billboard 200. “Hungry Heart” became his first Top 10 single, reaching #5. The band went on tour and this also marked his first set of shows outside North America.

After the tour, Springsteen disbanded the E Street Band, took a two-year break, and retreated to a farmhouse in Colts Neck, New Jersey. During this quiet time, away from crowds, Springsteen worked on acoustic, introspective music in his bedroom and pressed record on a four-track cassette recorder. Playing all instruments himself, he ended up making his sixth studio album called Nebraska.

“The songs of Nebraska were written quickly, all rising from the same ground. Each song took maybe three or four takes to record. I was only making demos,” said Springsteen. “These songs were the opposite of the rock music I’d been writing. They were restrained, still on the surface, with a world of moral ambiguity and unease below. The tension running through the music’s core was the thin line between stability and that moment when the things that connect you to your world, your job, your family, your friends, the love and grace in your heart, fail you. I wanted the music to feel like a waking dream and to move like poetry. I wanted the blood in these songs to feel destined and fateful.”

The cost of Nebraska was “about a grand” to make, then he went into the studio, brought in the band, re-recorded and remixed everything. “Nebraska entered respectably on the charts, got some pretty nice reviews and received little to no airplay. For the first time, I didn’t tour on a release,” said Springsteen.

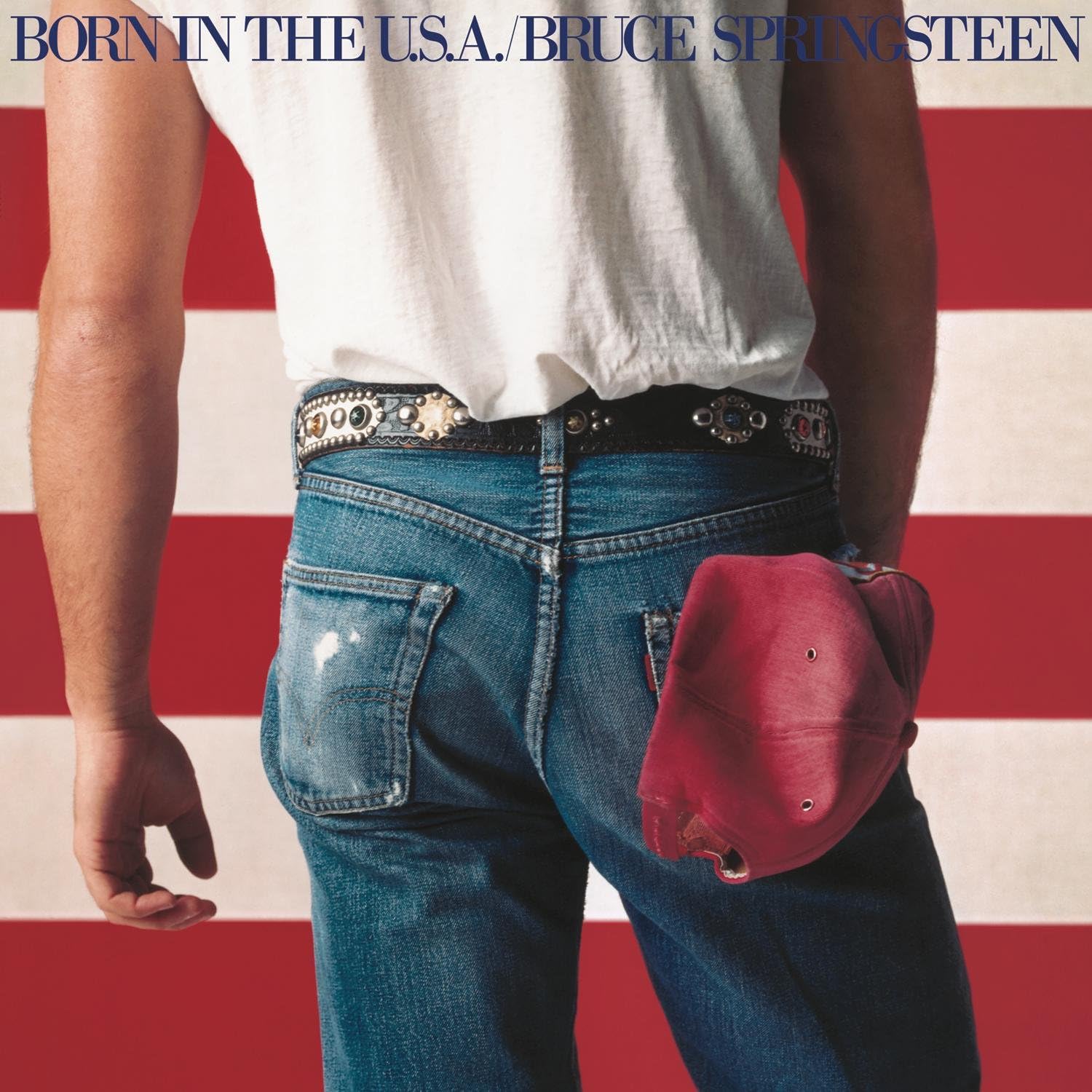

Nebraska and the first half of his next album, Born in the U.S.A., were recorded at the same time.

“For the follow-up to Nebraska, which contained some of my strongest songs, I wanted to take its same themes and electrify them… I copped ‘Born in the U.S.A.’ straight off the title page of that Paul Schrader script. The script was a story of the trials and tribulations of a local bar band in Cleveland, Ohio. The film would later be released as Light of Day, featuring my song of the same name, my polite attempt at paying Paul back for my fortuitous and career-boosting theft,” said Springsteen.

Much of Born in the U.S.A. was recorded with the full E Street Band over two years in New York City, with guitarist Nils Lofgren replacing Steven Van Zandt, who wanted to pursue a solo career. There were 70-90 songs on the table, but in the end, the “important pieces” made the record. Patti Scialfa joined the E Street Band for the Born in the U.S.A. Tour, providing backup vocals.

“‘Born in the U.S.A.,’ ‘Working on the Highway,’ ‘Downbound Train,’ ‘Darlington County,’ ‘Glory Days,’ ‘I’m on Fire’ and ‘Cover Me’ were all basically completed in the very early stages of the record. Then brain freeze settled in I was uncomfortable with the pop aspect of my finished material and wanted something deeper, heavier, and more serious. I waited, I wrote, I recorded, then I waited some more. Months passed in writer’s block, with me holed up in a little cottage I’d bought by the Navesink River, the songs coming like the last drops of water being pumped out of a temporarily dry well. Slowly, ‘Bobby Jean,’ ‘No Surrender’ and ‘Dancing in the Dark’ joined my earlier work,’ said Springsteen.

Lyrically: Dancing in the Dark by Bruce Springsteen

“Then, very late to the party came ‘Dancing in the Dark.’ One of my most well-crafted and heartfelt pop songs, ‘Dancing’ was ‘inspired’ one afternoon when Jon Landau stopped by my New York hotel room. He told me he’d been listening to the album and felt we didn’t have a single, that one song that was going to throw gasoline on the fire. That meant more work for me, and for once, more work was the last thing I was interested in. We argued, gently, and I suggested that if he felt we needed something else, he write it.” recalled Springsteen.

“That evening I wrote ‘Dancing in the Dark,’ my song about my own alienation, fatigue and desire to get out from inside the studio, my room, my record, my head and… live. This was the record and song that’d take me my farthest into the pop mainstream.”

I get up in the evenin’

And I ain’t got nothin’ to say

I come home in the mornin’

I go to bed feelin’ the same way

I ain’t nothin’ but tired

Man, I’m just tired and bored with myself

Hey there, baby, I could use just a little help

The opening lyrics of “Dancing in the Dark” describes a feeling of someone being stuck in a boring routine, something many people can relate to. Springsteen sings about sleeping all day, going out and coming home the next morning, potentially seeing only darkness. The days feel the same with no difference from yesterday to today. When he admits being tired and bored with himself, he’s talking more than just being physically tired. He’s emotionally drained and doesn’t even enjoy his own company. But then he asks for help, recognizing that a connection with another person might be the way to break free.

You can’t start a fire

You can’t start a fire without a spark

This gun’s for hire

Even if we’re just dancin’ in the dark

When Landau said he wanted “one song that was going to throw gasoline on the fire,” Springsteen took this literally as the spark needed to complete the job at hand. He was a “hired gun,” who is a person who is paid to perform a specific job or task, to just crank out another song.

“You can’t start a fire without a spark” lyrically means nothing happens without taking action. You need to do something to create change, not just think about changing. And in order to create change, movement is needed. “Even if we’re just dancin’ in the dark” suggests that even if you don’t know where you’re going, it’s still worth attempting. Taking action is better than doing nothing.

Messages keeps gettin’ clearer

Radio’s on and I’m movin’ ’round my place

I check my look in the mirror

Wanna change my clothes, my hair, my face

Man, I ain’t gettin’ nowhere

I’m just livin’ in a dump like this

There’s somethin’ happenin’ somewhere

Baby, I just know that there is

He’s aware of his unfulfilling current circumstances but has started to make a move. He wants a new identity and can see who he wants to become, but needs someone to further ignite him to pull him out of his own space to this “somethin’ happenin’ somewhere” place.

You sit around gettin’ older

There’s a joke here somewhere and it’s on me

I’ll shake this world off my shoulders

Come on, baby, the laugh’s on me

Days go by when you just think about wanting something new. Time slips away without accomplishing anything meaningful. The self-deprecating humour and the self-imposed weight continually pulls you down and lead nowhere.

Stay on the streets of this town

And they’ll be carvin’ you up alright

They say you gotta stay hungry

Hey baby, I’m just about starvin’ tonight

I’m dyin’ for some action

I’m sick of sittin’ ’round here tryin’ to write this book

I need a love reaction

Come on now, baby, gimme just one look

If you stay where you are and keep doing what you’re doing, you will get the same results. Eventually you will break down and be torn apart. One has to stay hungry, not just for success, but for connection and love, something he is starving for. He’s dying for action, movement, something to feel instead of this repetitive thinking. He’s tired of sitting alone, trying to figure out his life. He desperately wants to be noticed, even if it’s with just one look.

You can’t start a fire

Worryin’ about your little world fallin’ apart

The final chorus delivers the song’s core philosophy. Being consumed by worry or anxiety about how things may turn out stalls your progress. Worry, of any size, extinguishes any spark of energy. You must have the desire to move forward, to reach out, and take action despite the uncertainty.

“A songwriter writes to be understood,” said Springsteen.

“Sometimes records dictate their own personalities and you just have to let them be. That was Born in the USA. I finally stopped doing my hesitation shuffle, took the best of what I had and signed off on what would be the biggest album of my career. Born in the USA changed my life, gave me my largest audience, forced me to think harder about the way I presented my music and set me briefly at the center of the pop world.”

After rejecting Jeff Stein’s first version, Springsteen hired Brian De Palma, director of Scarface, to reshoot the “Dancing in the Dark” music video. On opening night of the Born in the U.S.A. tour, June 29, 1984, at the Civic Center in St. Paul, Minnesota, Springsteen filmed it with a pre-selected audience member, Courteney Cox, later of Friends and Scream, who he pulled onto the stage to dance.

“We’d spent the afternoon filming ‘Dancing in the Dark,’ our first formal music video,” Springsteen recalled. “I’d always been a little superstitious about filming the band. I believed the magician should not observe his trick too closely; he might forget where his magic lay. But MTV had arrived.”

“I did not want to be the one. I don’t want to dance in front of 30,000 people! It was a full concert, and we performed the song twice, back-to-back,” recalled Courteney Cox. “God. Did you see my dance? It was pathetic. I’m not a bad dancer, but that was horrible. I was so nervous.”

“Dancing in the Dark” became Springsteen’s most successful single ever, spending four weeks at number two on the Billboard Hot 100 and winning him his first Grammy for Best Male Rock Performance. The video became iconic, mainly for the dance moves, and won Best Stage Performance at the 1985 Video Music Awards.

“We did that video in about three or four hours. Lip-syncing is one of those things—it’s easy to do, but you wonder about the worth of doing it,” said Springsteen. “That video was great, though, because I noticed that most of the people that would come up and mention it to me were people who hadn’t heard my other stuff. Very often, they were real little kids.”