Before the world heard him, Marvin Gaye was Marvin Pentz Gay Jr.

In 1956, between the Korean and Vietnam Wars, the 17-year-old enlisted in the Air Force to escape the strict parenting and abuse of his cross-dressing, alcoholic father, a Pentecostal preacher. He had dreamed of becoming an aviator since childhood. “I had tremendous interests in aviation,” he later said. “I could tell you what any plane was without even looking at it, by the sound of its engines.”

While relieved to be away from home, he was unmotivated by the menial tasks of military life and became uncooperative. Within eight months, in mid-June 1957, he was back home in Washington, D.C., with a general discharge.

His discharge papers documented him as “a constant problem” who “required constant supervision.” His Commander’s report stated, “Airman Gay is uncooperative, lacks even a minor degree of initiative, shows very little interest in his assigned duties, and does nothing to improve his job knowledge… further retention in the service would be a waste of time, effort and money.”

At 18, his dream of flying was grounded. “I was torn between two desires,” he said. “I wanted to become an aviator, and I wanted to become a great singer.” He turned his focus to singing. “I decided that, come hell or high water, I was going to make it as a pop singer.”

He reunited with friends Reese Palmer, Chester Simmons, and James Nolan and formed The Marquees, a doo-wop group. “We had a little group. We were singing around town, Washington, D.C., and we called ourselves the Marquees. We always patterned ourselves after the Moonglows. Boy, we loved their sound… we really sang, man, like the Moonglows,” said Gaye.

The Marquees started singing on street corners, performing at talent shows at the Lincoln Theater, and competing at high school battles of the bands. They eventually caught the attention of Bo Diddley, known as “The Originator” for his role in bridging blues music to rock & roll.

Diddley had moved from Chicago to Washington, D.C., in 1957 and built a recording studio in his basement. He began working with the Marquees and secured a recording session with Okeh Records in New York City. In September 1957, they recorded “Wyatt Earp” and “Hey Little School Girl.” The record was released in November with no promotion and received minimal attention.

The Moonglows, the doo-wop group that The Marquees aimed to emulate, split up in 1957. Founding member Harvey Fuqua, who helped establish early rock and roll, was looking to form a new group and was introduced to The Marquees by Diddley. In 1958, “Harvey and the New Moonglows” was created with members of The Marquees.

“We were singing around and Harvey popped through there. Harvey, the leader of the Moonglows, he heard us and he thought that we sounded quite a bit like the group, the original group, and they had long since dispersed, and he thought that we would make a nice replacement… so we got together, we went on the road, and we were fairly successful. We had lots of fun, really,” said Gaye.

Harvey and the New Moonglows recorded several songs in 1959, including “Mama Loochie” and “Twelve Months of the Year.” However, the group disbanded in 1960.

A new start in Detroit, with a new name

In 1960, after the Moonglows disbanded, Fuqua recognized Gay’s potential and proposed that they move to Detroit. The city was beginning to emerge as a music hub, buzzing with the R&B sounds coming out of the newly founded Motown Records. For Gay, the move was a chance to pursue his dream of becoming a pop singer and an opportunity to leave his home life behind.

Upon their arrival in Detroit, Fuqua leveraged his relationship with Gwen Gordy, sister of Motown founder Berry Gordy, to gain direct access to the label’s founder. Rather than navigating the typical audition channels, Fuqua brought Gay straight to Gordy and pitched him as a talent worth signing. On September 19, 1960, just months after arriving in the city, Gay secured a recording contract with Motown’s Tamla subsidiary.

Motown had parties where artists would perform impromptu. At the Christmas party in 1960 is where Bill “Smokey” Robinson, one of the early Motown stars, saw and heard Marvin Gay for the first time. “He was singing it to himself. But everybody started to gather around, especially the ladies,” said Robinson, “because he had that voice.”

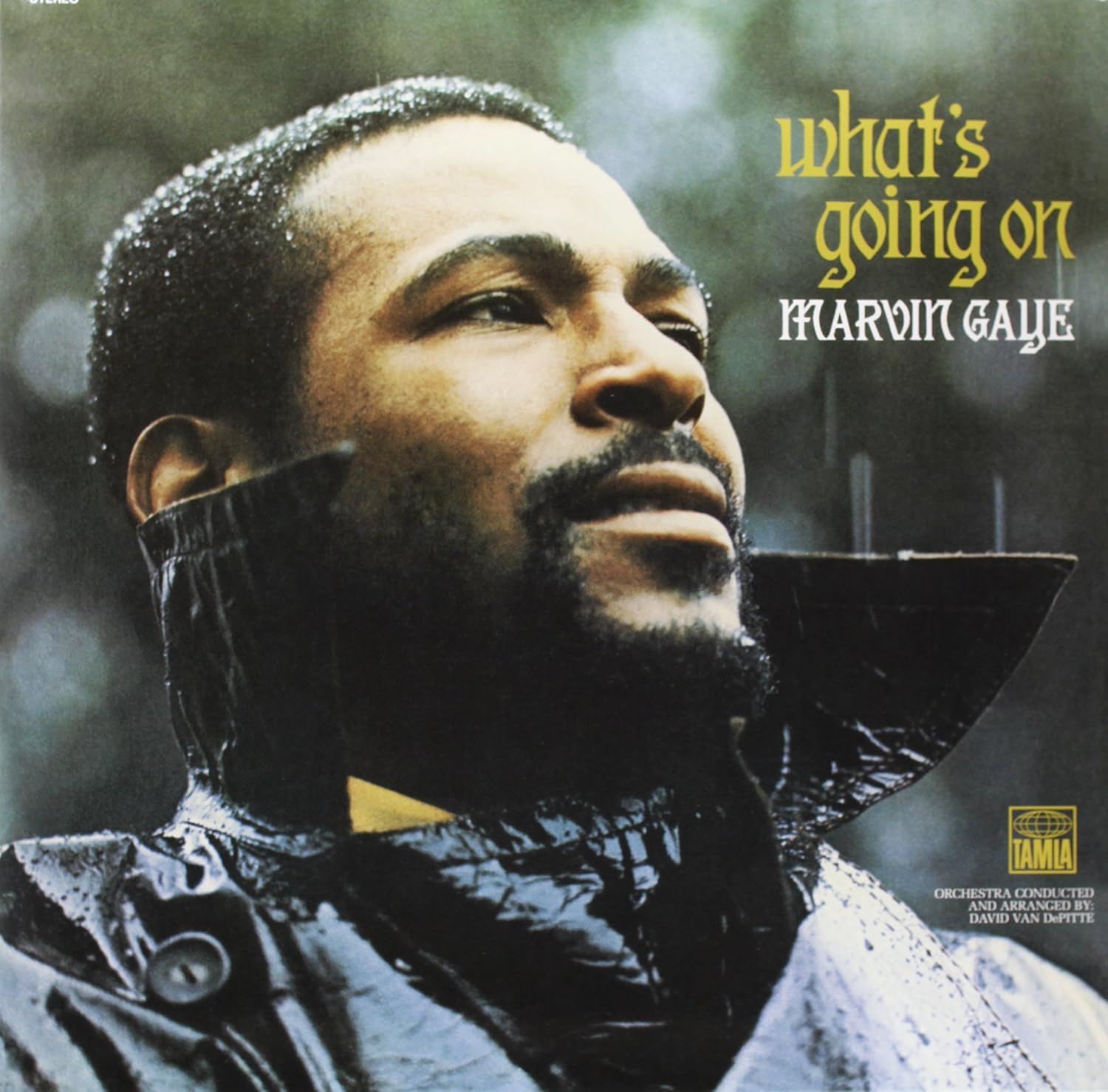

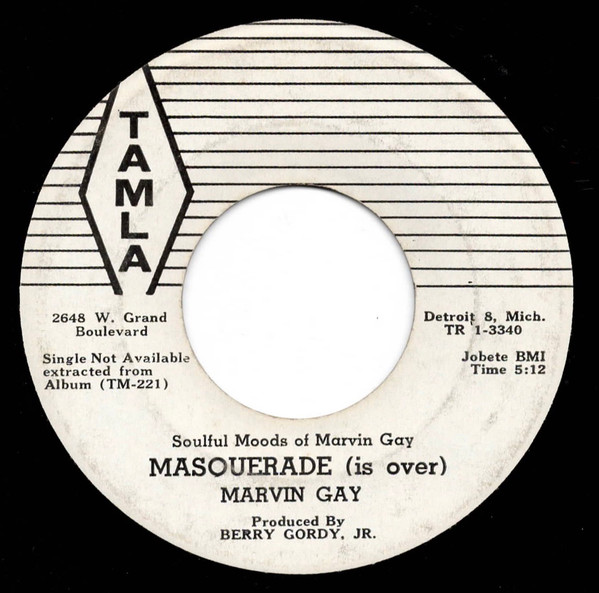

Gay began recording music with Motown in early 1961, focusing initially on jazz and traditional pop rather than the R&B sound the label was becoming known for. In May, a limited-run promotional single under his name featuring “Masquerade (Is Over)” and “Witchcraft” was sent to radio stations and industry insiders to generate interest ahead of his debut album.

In the same month, Gay transformed his identity, adding an “e” to his surname to become Marvin Gaye. A pivotal personal decision that distanced him from his father and dispelled rumours about his sexuality.

Gaye’s pop star dream had become a very specific vision. He wanted to be a Motown version of Frank Sinatra. “Every woman in America wanted to go to bed with Frank Sinatra,” he said. “He was the king I longed to be. My greatest dream was to satisfy as many women as Sinatra.”

On June 8, 1961, Gaye’s debut album, The Soulful Moods of Marvin Gaye, arrived, featuring jazz and R&B songs. Despite this effort, neither his singles nor the album charted. The lack of commercial success started friction between Gaye’s artistic ambitions and Gordy’s emerging business model. The label was building itself on rhythm and blues for teenagers, not on crooners sitting on stools.

By summer 1962, nearly a year after his debut album, Gaye was considered by some at Motown “the least likely hit maker.” A forced compromise with Gordy would change everything. Gordy insisted Gaye reinvent himself as an R&B artist, and he reluctantly agreed.

“The industry is full of all kinds of personalities… For me, I believe in living and letting live. I think love is really the key. I’m the kind of guy who likes people. I love people, I love nature, I love the rain, the sun, simple things. I don’t go for fancy stuff. I enjoy what’s basic and real,” said Gaye. “I think a performer needs humility, real humility, not an act. They need to be good inside, and that comes from childhood. It’s not something you can fake in public; it has to be part of who you are. If you have that, and you have the talent, and a few other qualities… then you have a pretty good chance of making it.”

With producer Mickey Stevenson, Gaye co-wrote and recorded “Stubborn Kind of Fellow.” The song was released on July 23, 1962, and entered the charts on October 14, peaking at No. 8 on the R&B chart and No. 46 on the pop chart by December.

The success transformed Gaye from a liability into Motown’s latest asset. Gordy recognized that Gaye could become a heartthrob with crossover appeal. This positioned Gaye as a specific persona, no longer the sophisticated crooner he envisioned, but a romantic lead singer designed for a specific audience.

Once he cracked the charts and established momentum, the hits came quickly. “Hitch Hike” followed in early 1963, reaching the Top 40, and then “Pride and Joy” became his first pop Top 10 hit in April of that year.

The following year, Gordy added duets to his formula for Gaye. A duo with Mary Wells on the album “Together” produced “Once Upon a Time” and proved the strategy worked. When Smokey Robinson handed Gaye “Ain’t That Peculiar” in 1965, it became one of his biggest solo successes. 1966 brought “It Takes Two” with Kim Weston, and in 1967, when Gaye became known as the “Prince of Soul,” he stepped into the studio with Tammi Terrell and everything changed.

Their chemistry was undeniable. The duo released “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” a song co-writer Nick Ashford described as capturing the “physical attraction” between them.

Tragedy struck when Terrell collapsed into Gaye’s arms during a performance at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia on October 14, 1967. She was rushed to the hospital and initially diagnosed with exhaustion, but later tests revealed a brain tumour.

Despite her deteriorating health, they continued recording together. Their 1968 album “You’re All I Need” produced standout hits including “You’re All I Need to Get By” and “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing.” They recorded one more album, Easy, in 1969. Terrell died in March 1970 at age 24.

Gaye was devastated. He withdrew from performing for a year and fell into deep depression, struggling with drug abuse. The loss shattered him, both personally and professionally.

“My heart was broken…. I could no longer pretend to sing love songs for people,” said Gaye.

Months of a showdown

“I saw what was happening in this country and I wasn’t doing a damn thing about it. I was tired of going out and getting the women to scream. I had to be more than a sex symbol. I had to be an artist,” said Gaye.

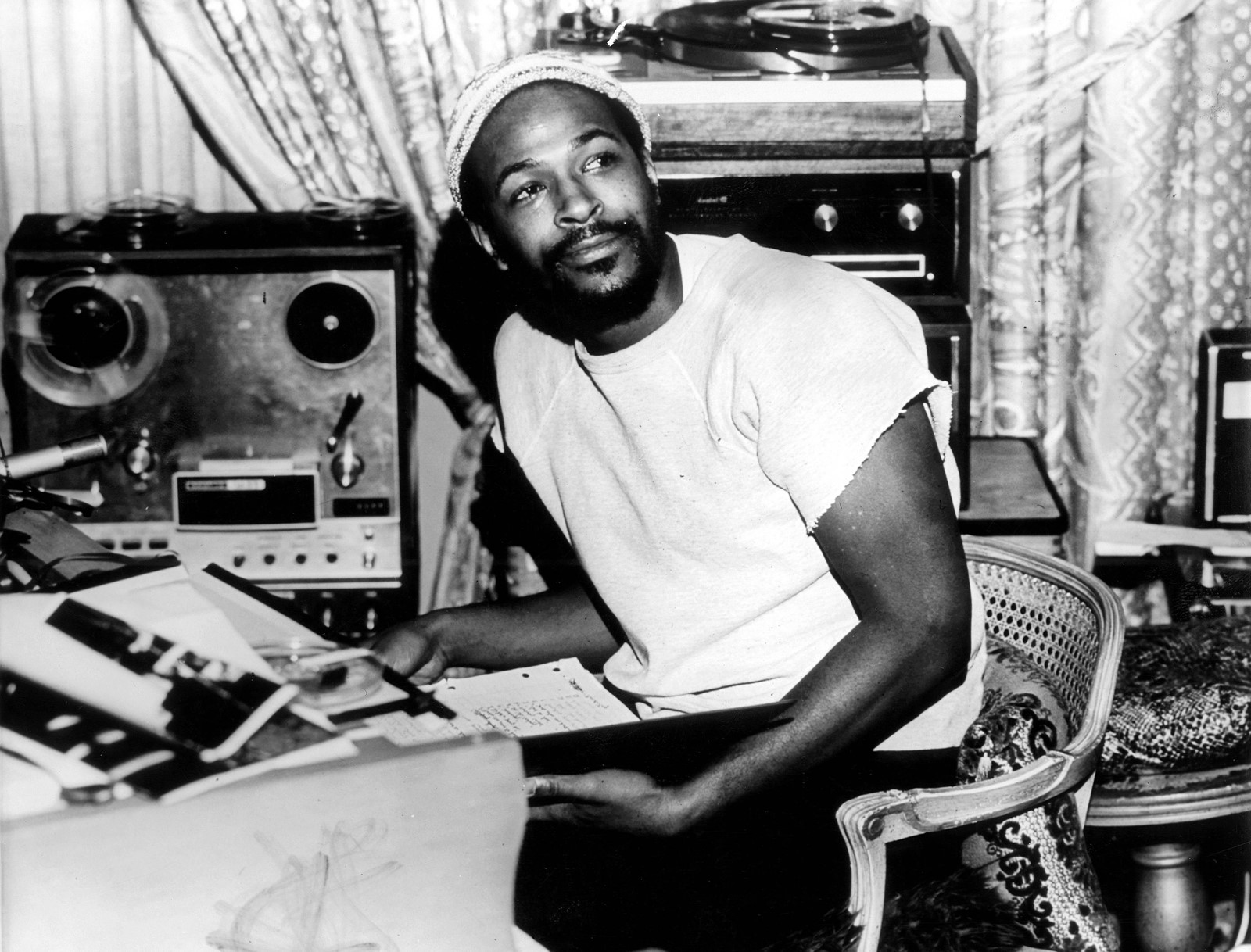

Motown wanted Gaye back in the studio, but he was unsure of his direction. Internally conflicted, he felt a change coming. Externally, he grew a beard. A move that represented a visible break from the clean-cut crooner that Motown had crafted.

“Black men weren’t supposed to look overtly masculine,” Gaye said. “I spent my entire career looking harmless, and the look no longer fit. I wasn’t harmless. I was pissed at America.”

“My phone would ring,” Gaye said, “and it’d be Motown wanting me to start working and I’d say, ‘Have you seen the paper today? Have you read about these kids who were killed at Kent State?’ The murders at Kent State made me sick. I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t stop crying. The notion of singing three-minute songs about the moon and June didn’t interest me.”

Frustrated emotions surfaced further in 1970 when Frankie, Gaye’s younger brother, returned home from serving in Vietnam with the Army. Gaye went back to Washington D.C. to be with him.

“Nights were the best,” Frankie recalled, “and we really became kids again as we stretched out in our beds, telling stories in the dark. Only now, Marvin wanted me to do the talking. He was full of questions, and they all had to do with my experiences in Vietnam. He wanted to hear everything – what I saw, what I heard, what I felt.”

“The death and destruction I saw in Vietnam sickened me,” Frankie said. “The war seemed useless, wrong and unjust. I relayed all this to Marvin.”

“My blood started to boil. I knew I had something—an anger, an energy, an artistic point of view. It was time to stop playing games… I sorta saw the country headed for modern-day civil war… I felt the strong urge to write music and to write lyrics that would touch the souls of men,” said Gaye.

Gaye’s friend Renaldo “Obie” Benson of the Four Tops witnessed the police violence against students at UC Berkeley in May 1969. The impact wouldn’t leave him. “I started wondering what the fuck was going on? What is happening here?,” Benson said. “One question leads to another. Why are they sending kids so far away from their families overseas? Why are they attacking their own children in the streets here?.”

Benson pitched a song idea to the Four Tops that was inspired by his experience of witnessing the police violence, but the group wasn’t interested. Benson then took it to Joan Baez, but she turned it down, too. When Gaye heard the story, he connected to it and started shaping a song, drawing from his own conversations and the escalating social tensions.

Gaye entered the studio on June 1, 1970, to record what would become “What’s Going On,” finishing the song by September of that year.

Motown, specifically Gordy, wasn’t interested in the song. “Why do you want to ruin your career? Why do you want to put out a song about the Vietnam War, police brutality and all of these things? You’ve got all these great love songs. You’re the hottest artist, the sex symbol of the sixties and seventies,” said Gordy.

“It should’ve been my moment of artistic triumph, but Berry and the promoters in the Motown marketing meetings ridiculed ‘What’s Going On’,” said Gaye.

“He knew where he was and who he was so long before the company even allowed him to be, because it sat there for a year. It was so new—they couldn’t hear it, they couldn’t understand it, they couldn’t believe this message was going to reach the masses,” said Motown songwriter Valerie Simpson. “It’s a treasure that sat on a shelf for a year because we were waiting for them to grow up to where he was musically.”

“At that time it was so controversial. I think they wanted to keep the Motown platform not political, more just love themes,” said songwriter Nick Ashford.

“Put it out or I’ll never record for you again,” said Gaye to the execs at Motown when they refused to release the single.

Barney Ales, Motown’s general manager, stated, “I remember a meeting with Berry Gordy in Los Angeles, and he was complaining about Marvin being up in the mountains, talking to God, not finishing his album. By the start of ’71, we had nothing new, so I got together with our quality control head, Billie Jean Brown, and we decided to release ‘What’s Going On’ as a single. That’s all we had.”

After a power struggle, “What’s Going On” was released on January 21, 1971 with a limited pressing of 100,000 copies. This quickly became Motown’s fastest-selling single.

“I was in Detroit when Berry called and said, ‘How could you release that record? It’s the worst I’ve ever heard.’ But it exploded – we couldn’t keep up with the orders,” said Ales. Marvin had captured the mood of the time. When he delivered the album and we shipped it in May, the same thing happened. It went Top 10 in the pop charts in five weeks, which in those days was amazing.”

“Marvin definitely put the finishing touches on it,” said Benson. “He added lyrics, and he added some spice to the melody. He added some things that were more ghetto, more natural, which made it seem more like a story than a song. He made it visual. He absorbed himself to the extent that when you heard the song you could see the people and feel the hurt and pain.”

Lyrically: What’s Going On by Marvin Gaye

The start of the “What’s Going On” puts you right on a busy street, immersed in spontaneous, happy chatter between people. The voices belong to Bobby Rogers of the Miracles, musician and songwriter Elgie Stover, and two of Gaye’s friends, Lem Barney and Mel Farr, who played for the Detroit Lions.

“He says, ‘Lem, you take this part,’ ‘Mel, you take this part,'” Barney recalled. “The next time you listen to it, in the beginning when it says, ‘Hey, brother, what’s happening?! Solid! Right on! Mother, mother …’ We backgrounded him on the whole song, man!”

The setup was deliberate. Gaye wanted you to hear the reality of everyday street life and the sounds of community.

“The song was exactly about what was happening in this world, you know?” Farr said. “What he did, he just wanted to put it in lyrics. He wrote everything. He did it all. He was a very socially conscious individual about things being equal here.”

“For the first time I really felt like I had something to say,” said Gaye.

Mother, mother

There’s too many of you crying

Brother, brother, brother

There’s far too many of you dying

You know we’ve got to find a way

To bring some lovin’ here today, yeah

Gaye’s voice entered smooth and intentional, cutting through the chatter. When “What’s Going On” was recorded, America was in profound crisis. Nearly 50,000 Americans had died in Vietnam, hundreds of thousands more wounded, and a generation was rejecting the war through protests, draft resistance, and demands for peace. The mothers were crying, and brothers were dying. Gaye suggested that the only way forward was to show love for each other.

Father, father

We don’t need to escalate

You see, war is not the answer

For only love can conquer hate

You know we’ve got to find a way

To bring some lovin’ here today

When Gaye calls out “Father, father,” he’s pleading with those in power who need to listen and understand what’s happening, from the President and military leaders to spiritual authorities. But the word “father” also carried weight for Gaye, extending to his own dysfunctional relationship with his father.

Gaye’s message is clear: the fight does not need to escalate any further. The answer is not more violence or hurt, but love. There must be a way to find a healthy path forward.

Picket lines and picket signs

Don’t punish me with brutality

Talk to me

So you can see

Oh, what’s going on (What’s going on)

What’s going on (What’s going on)

By the time Gaye finished writing “What’s Going On” in September 1970, police brutality against demonstrators was rampant. On May 4, National Guard troops fired on student anti-war protesters at Kent State University in Ohio, killing 4 and wounding 9. Three days later on May 8, the Hard Hat Riot broke out when construction workers, with apparent police cooperation, attacked anti-war demonstrators in New York City, injuring around 100. On August 29, the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department attacked Chicano anti-war marchers with tear gas and clubs during the Chicano Moratorium, killing 3 people.

The lyrics “Don’t punish me with brutality / Talk to me / So you can see / Oh, what’s going on,” suggests that if fighting is not the answer, then a conversation is. Gaye calls for a peaceful exchange where people can understand each other’s perspectives without inflicting pain or brutality. Communication replaces confrontation as the path to understanding.

Mother, mother

Everybody thinks we’re wrong

Oh, but who are they to judge us

Simply ’cause our hair is long

Oh, you know we’ve got to find a way

To bring some understanding here today

Gaye addresses the experience of discrimination in a conversational tone, looking for understanding but getting judgement in return, both for beliefs and appearance. He professes, almost preaches, that love is the way.

The closing verse returns to a conversational tone, which Gaye suggests is how one could reach a peaceful resolution.

The song ends by returning to where it started, now with solidarity with the chatter of “Right on, baby, right on.”

“In this life, I love music. and music is my life. It’s all I know,” said Gaye.

Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” peaked at No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 and No. 1 on the R&B chart. It has been included in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s “500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll,” honoured by Rolling Stone as one of the “500 Greatest Songs of All Time,” and was added to the Library of Congress National Recording Registry in 2003, which preserves recordings deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”