“I’ll tell you what I’m talking about. I’m no girl, I’m a woman. Do you hear? I’m not your wife or your mother or even your mistress. I am your employee. As such, I expect to be treated equally, with a little dignity and respect,” declares Violet Newstead, played by Lily Tomlin in the 1980 comedy 9 to 5, to her “sexist, egotistical, lying, hypocritical bigot” boss Franklin Hart.

Shortly after this confrontation, Violet is joined by Judy Bernly, played by Jane Fonda, and Doralee Rhodes, played by Dolly Parton, at Charlie’s, the local bar. The three bond over their workplace frustrations: Violet has been passed over for a promotion again, Doralee is fed up with constant sexual harassment from their boss, and Judy is outraged after witnessing a colleague’s unjust firing. During their evening together, fueled by anger, frustration, a few too many drinks, and a joint, they begin fantasizing about getting revenge on their tyrannical boss.

Violet, Judy, and Doralee essentially hold Franklin Hart captive in his own home through a series of comedic mishaps and take control of the office. They forge his signature and type up a memo to implement progressive changes under the boss’s name, reforms that make the workplace more efficient and happier, such as equal pay, flexible working hours, an on-site daycare center, job-sharing programs, office redesign, and mental health support.

When the company chairman witnesses the dramatic improvements in productivity, morale, and profitability, he doesn’t recognize the women’s leadership but instead promotes Franklin Hart and implements their reform ideas company-wide.

“What are we gonna do? We’ve come this far, haven’t we? This is the beginning. Here’s to the beginning,” said the trio at the end of the movie, indicating that their fight for workplace equality and women’s rights was just getting started.

The 9to5 Movement

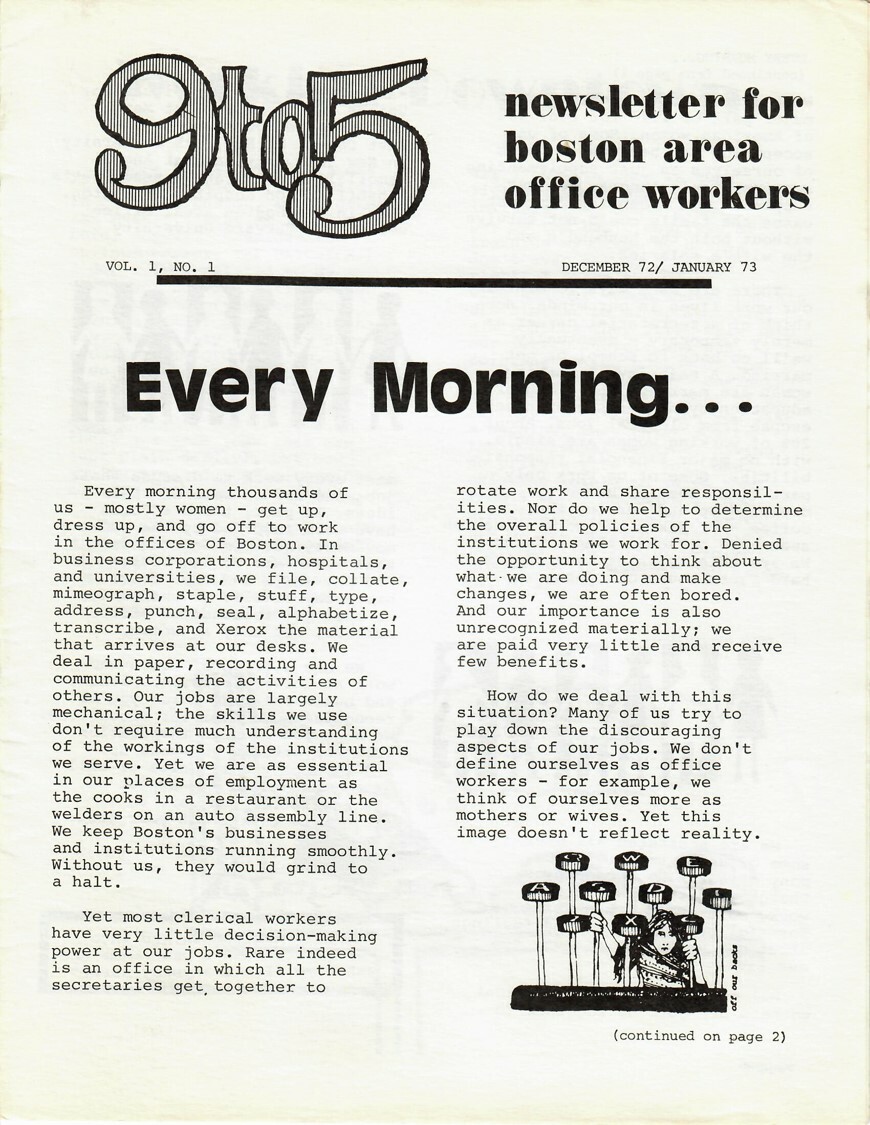

The idea behind the movie came from Jane Fonda, who witnessed the movement that was co-founded by Karen Nussbaum and Ellen Cassedy in Boston in 1973 called “9to5, National Association of Working Women.” While working as secretaries at Harvard University, Nussbaum and Cassedy started a newsletter called “9to5: Newsletter for Boston Area Office Workers” in December 1972 before formally establishing the organization in 1973. The group was dedicated to improving the working conditions for women office workers who faced discrimination, low wages, and limited advancement opportunities.

Their motivation came from direct experience with being “invisible” in the workplace. Nussbaum recalled, “It was a kind of job where you were just not seen. You were just part of the wallpaper. “I remember sitting at my desk at lunch one day, and a student came in—I worked at a university—looked me dead in the eye and said, ‘Isn’t anybody here?’ And it was those kinds of things that just got under your skin a lot.”

“Office workers were invisible, but we were the largest sector of the workforce. There were 20 million women office workers. One out of three women worked in an office in those days, but there had been no cultural depictions of women in this job,” said Nussbaum.

“The bosses acted as if women were unqualified to do anything except type, file, staple papers, collate, alphabetize and make photocopies and coffee,” said Cassedy. “Worse, when they weren’t treating us like decorative objects, they treated us as if we were invisible.”

“The most common task for most clerical workers was probably getting coffee for the boss,” said Nussbaum. “This notion that you were there as the office wife, to do anything that was asked of you—we didn’t know how to express what was wrong with that, but we sure felt like it was wrong. People were quietly seething.”

“If we don’t fight for dignity and respect on the job, who’s going to fight for us?” Nussbaum said.

Fonda knew Nussbaum through their shared involvement in the anti-Vietnam War movement during the early 1970s. When the war ended in 1975, Fonda decided that making a movie about the women’s workplace movement would be the most impactful way to contribute to women’s labour rights.

“Women work as they have to. They are getting angry, and they’re beginning to organize all around the country, and I support them, and I’m gonna make a movie,” stated Fonda about her intentions before the movie even shot a scene.

Nussbaum recalled, “I knew Jane Fonda from my days in the peace movement. We were in the same organization, and then in 1975 when the war ended, Jane wanted to make a contribution to the work of 9to5 in the best way she knew how, which was to make a major motion picture. And so we talked for a couple of years about what that would look like, and she met with a lot of our members… Jane Fonda understood and tapped into—and that also the way her genius about this was understanding that it had to be real. It had to really reflect the way women talked, what their issues were, how they felt about it, and it couldn’t be didactic. That it had to be a comedy – that the only way you could bring people into it was by poking fun.”

“Jane was asked, ‘Are you lighting a fire under the desks and the offices of America?’ and she said, ‘No, secretaries are lighting those fires, and we are just fanning the flames,'” stated Cassedy.

“There’s already an eruption in the offices of America,” said Fonda. “There’s a very powerful movement growing among secretaries. It’s called Women Working, the National Association of Women Office Workers, mainly made up of women who believe that women should be paid the same as men for doing the same work and be treated with more respect. And we’re trying to reflect in the film the fact that the work that clerical workers do… is important work. You can run a company without a boss but not without a secretary. Women feel their work is important. They know that it’s skilled work, and they want to be treated with respect. That manifests itself both in the paycheck and in their treatment in the office. What’s unusual about our film is that it deals with this very serious subject as a comedy.”

“My producing partner Bruce Gilbert and I decided we wanted to make a movie about it, and then one night I saw Lily Tomlin in her one-woman show, In Search of Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe, and I basically fell in love. And I said, ‘I can’t make a movie about secretaries unless she’s one of the secretaries.’ And this is a true story: on the way home I turned on the radio, and Dolly Parton was singing ‘Two Doors Down,’ and my hair stood on end. She’d never made a movie. I thought, ‘Oh my lord, Dolly, Lily, and Jane.’ Okay, but it’s gonna have to be a comedy, and I’m gonna have to have the least interesting role. It took a year to convince them to do it, and it was a huge success,” said Fonda.

“Nothing is fun if it’s not controversial,” stated Fonda. “The movie was married to a movement.”

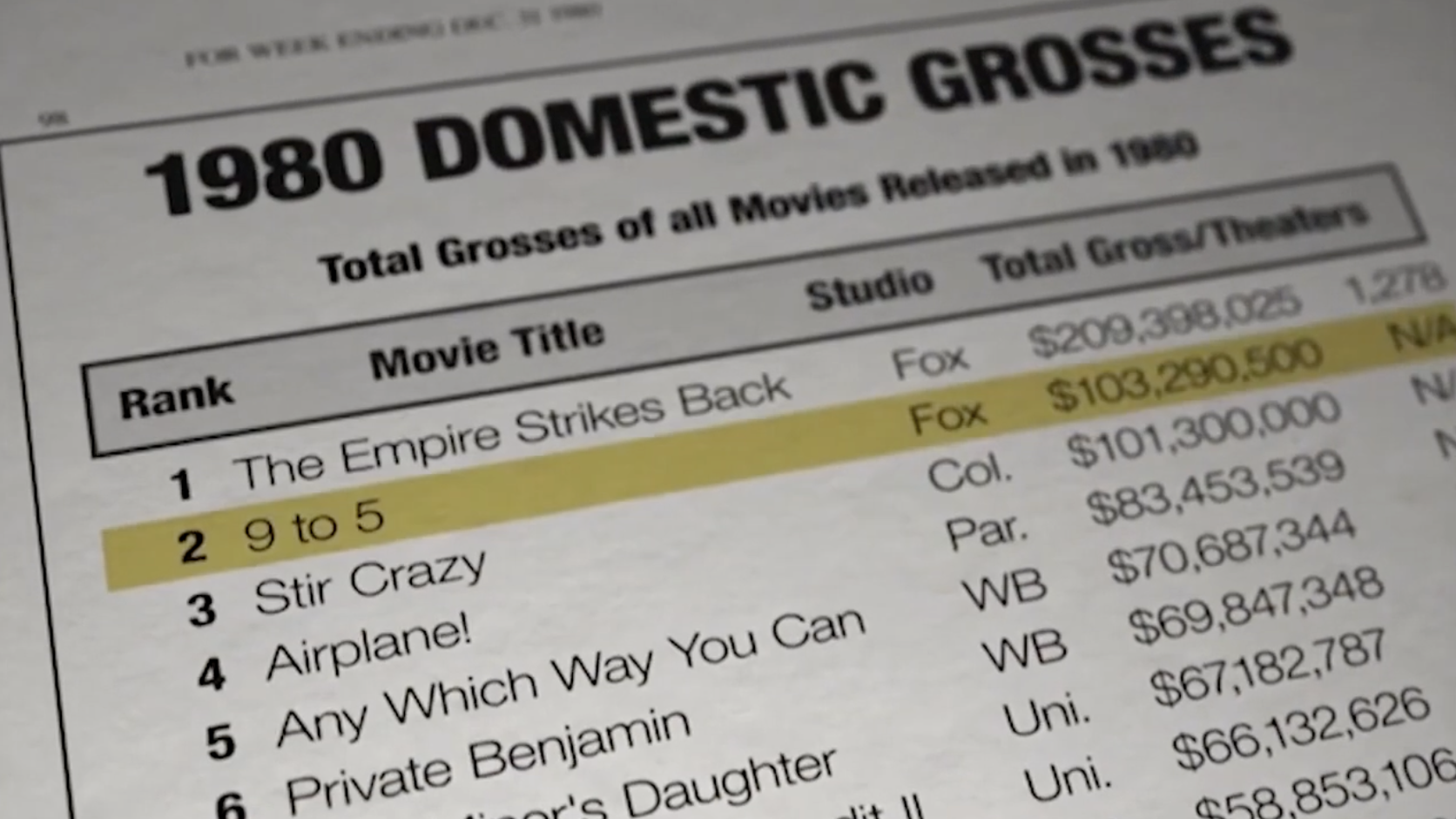

The film 9 to 5 was released on December 19, 1980, and became a commercial success, earning over $100 million worldwide and becoming the third highest-grossing film of 1981.

The movie received an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Song (‘9 to 5‘ by Dolly Parton) and a Writers Guild of America nomination for Best Comedy Written Directly for the Screen.

“It just completely changed the debate in the country,” said Nussbaum. “Women walked into the movie theatre without a political agenda. And you walk out of the movie theatre and you think: ‘That’s outrageous.’ You’re no longer questioning whether there’s such a thing as discrimination. You’re past that, and you’re ready for solutions.”

“The film was huge. It was the greatest thing that could ever have happened to us. The film ended the debate over whether there was discrimination. At the beginning, we had to have conversations with people about whether there was discrimination. By the time the film had happened, that wasn’t true anymore. The question was, “Now, what do we do about it?” I remember being on the bus one time after the movie came out, and I heard one woman saying, “So I said to him, ‘No, I will not make your coffee, I just saw 9 to 5,’” said Cassedy.

“We didn’t know that 9 to 5 was going to be a box office smash, we didn’t know it was going to become an iconic movie that was probably the most successful political movie ever made. And we certainly didn’t have any idea of how the song would become an anthem for the entire women’s movement,” said Nussbaum.

Acrylic nails clicking together sound like a typewriter

“I want to be a star. I would like to be a superstar,” said Dolly Parton during a 1977 interview with Barbara Walters. “Do you think that the superstardom will be here, let’s say, in five years?” asked Walters. “Yes,” said Parton.

Parton made her film debut in 9 to 5 as Doralee Rhodes and only agreed to play the part if she could write the theme song. “I said, ‘Well, this is a good opportunity, but I’ll only do it if I can write the theme song,'” said Parton.

In the years leading up to 9 to 5, Dolly Parton was already one of country music’s biggest stars and a growing pop crossover name, with multiple No. 1 country singles and the pop hit ‘Here You Come Again.’ She was a familiar face on TV, so when she joined the cast in 9 to 5, she came in as a well-established celebrity, not a newcomer, and the movie-plus-song combination pushed her from big star to a global household name.

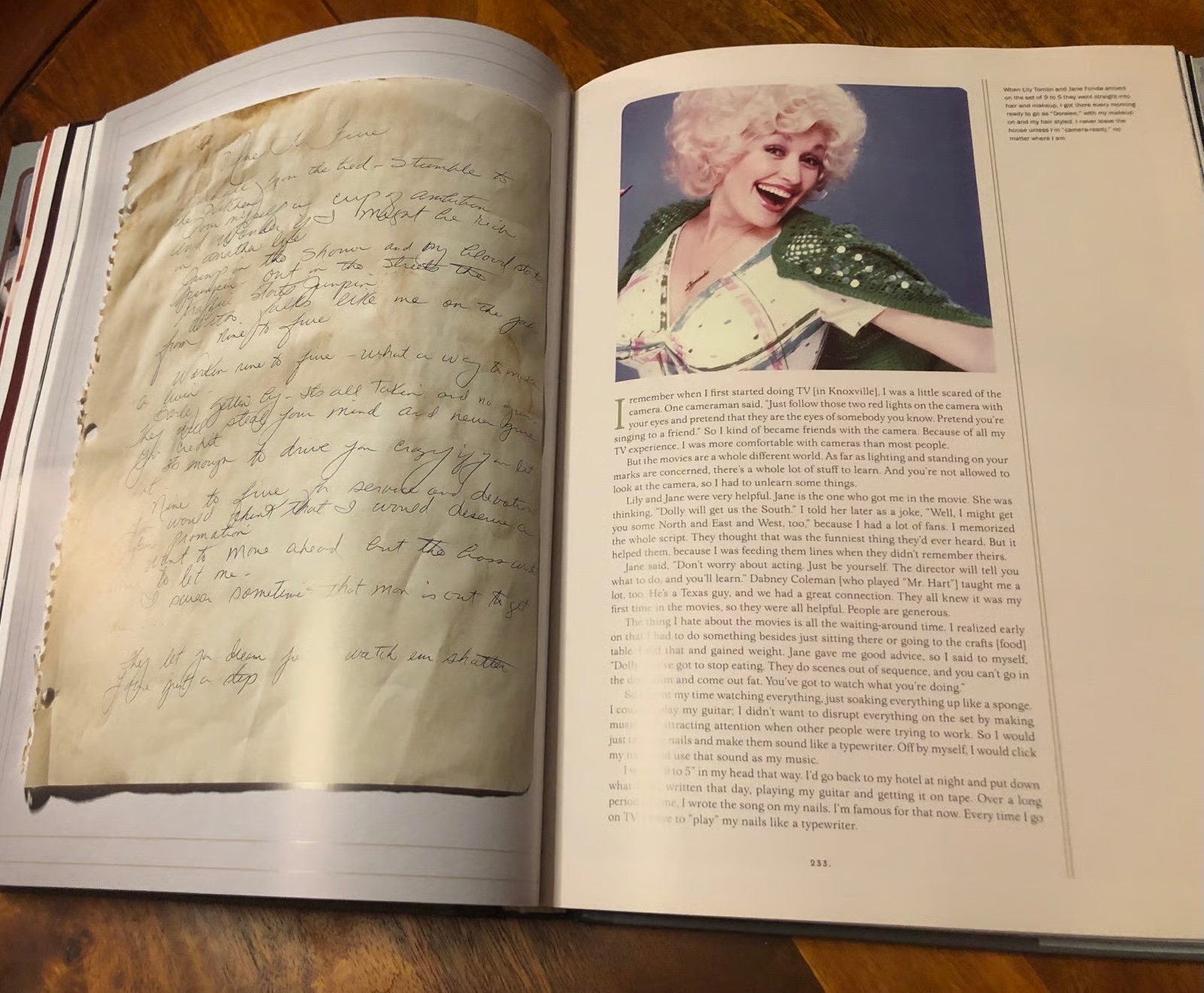

“Lily and Jane were very helpful. Jane is the one who got me in the movie. She was thinking, ‘Dolly will get us the South.’ I told her later as a joke, ‘Well, I might get you some North and East and West, too,’ because I had a lot of fans. I memorized the whole script. They thought that was the funniest thing they’d ever heard. But it helped them, because I was feeding them lines when they didn’t remember theirs,” said Parton.

“Jane said, ‘Don’t worry about acting. Just be yourself. The director will tell you what to do, and you’ll learn.’ Dabney Coleman [who played ‘Mr. Hart’] taught me a lot, too. He’s a Texas guy, and we had a great connection. They all knew it was my first time in the movies, so they were all helpful. People are generous.”

“What I found the hardest, most difficult to deal with, was all the time that it takes and those long hours… But I started putting my time to use, and I started writing songs and reading a lot, so it worked out okay. I wrote some good songs. I wrote the theme song, by the way, on the set,” said Parton.

“I spent my time watching everything, just soaking everything up like a sponge. I couldn’t play my guitar; I didn’t want to disrupt everything on the set by making music or attracting attention when other people were trying to work. So I would just play my nails and make them sound like a typewriter. Off by myself, I would click my nails and use that sound as my music.”

“I wrote ‘9 to 5’ in my head that way. I’d go back to my hotel at night and put down what I’d written that day, playing my guitar and getting it on tape. Over a long period of time, I wrote the song on my nails.” “After we recorded the song, I brought all the girls down that was on the show and I played my nails. So I have a credit on the back of the album that says, ‘nails by Dolly.'”

“Jane Fonda and I were just flabbergasted; we thought it was so great,” Tomlin said. “I said to Jane, ‘This will make the movie a hit, if nothing else.'”

The song ‘9 to 5’ was released as a single on November 3, 1980, about six weeks before the film’s U.S. release, and plays over the opening credits, serving as the movie’s main theme and eventual anthem for anyone who has felt undervalued.

Lyrically: 9 to 5 by Dolly Parton

“It just popped in my head one day, and it was when we did our first scene. I was writing this song. We were waiting in the Xerox room the first time we were together,” said Parton.

Tumble out of bed

And stumble to the kitchen

Pour myself a cup of ambition

And yawn and stretch and try to come to life

Jump in the shower

And the blood starts pumpin′

Out on the streets, the traffic starts jumpin’

For folks like me on the job from 9 to 5

These lyrics connect with millions of people who work traditional ‘9-to-5’ jobs and experience the morning routine and daily grind of another workday beginning.

Workin′ 9 to 5

What a way to make a livin’

Barely gettin’ by

It′s all takin′ and no givin’

They just use your mind

And they never give you credit

It′s enough to drive you

Crazy if you let it

The chorus emphasizes how workers are “barely gettin’ by” while their employers profit from their labour, as employees give their time and energy without receiving adequate recognition or compensation. The relatable workplace frustrations have the potential to ‘drive you crazy,’ but only ‘if you let it.’ This underlying message puts the power back in workers’ hands and empowers them to choose how to respond.

9 to 5

For service and devotion

You would think that I

Would deserve a fat promotion

Want to move ahead

But the boss won’t seem to let me

I swear sometimes that man is

Out to get me, hmmm

They let you dream

Just a watch ′em shatter

You’re just a step on the boss man′s ladder

But you got dreams he’ll never take away

In the same boat with a lot of your friends

Waitin’ for the day your ship′ll come in

And the tide′s gonna turn

And it’s all gonna roll you away

“I love how the song begins with pride – ‘Pour yourself a cup of ambition,'” said Nussbaum. “And then it goes to grievances – barely getting by, they always take the credit. It then goes to class conflict – you’re just a step on the boss man’s ladder. And then it ends with collective power – you’re in the same boat with a lot of your friends. So in the space of this wildly popular song with a great beat, Dolly Parton just puts it all together, all by herself.”

Yeah, they got you were they want you

There′s a better life

And you think about it, don′t you?

This lyrics capture the tension between feeling trapped in a job while maintaining hope for change.

It’s a rich man′s game

No matter what they call it

And you spend your life

Putting money in his wallet

These lyrics expose how workers spend their lives enriching their employers while the system itself is designed to benefit the wealthy, regardless of how it’s packaged or justified.

Parton had no shortage of material. She wrote 100 verses based on ‘real things that happened,’ though she knew some would never make the final cut.

“9 to 5” earned four Grammy nominations and won two, including Best Country Song and Best Country Vocal Performance, Female. It reached number one on the country charts in February 1981 and also topped both the pop and adult-contemporary charts, demonstrating how deeply the conversation about workplace equality resonated with audiences.